A clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris in this case) rests on its anemone home

Raja Ampat, Indonesia, August 2015

There are actually thirty different species of clownfish, also known as “anemone fish”, but one only ever sees a small number in popular culture and media. The species in this image is perhaps the one we are shown most frequently – and is the star of Finding Nemo.

Clownfish live in symbiosis with their anemone hosts.

The sea anemone protects the anemonefish from predators, as well as providing food through the scraps left from the anemone's meals and occasional dead anemone tentacles, and functions as a safe nest site.

In turn, the clownfish’s faecal matter provides nutrients to the anemone.

It has also been suggested that the clownfish’s bright coloring might lure small fish to the anemone, which then catches them.

Clownfish are impervious to the poison produced by anemones.

They are photographed so frequently and images of clownfish so common that it’s hard to get an original-looking photograph of them. So it’s nice that this one is so funny.

Raja Ampat, Indonesia, August 2015

There are actually thirty different species of clownfish, also known as “anemone fish”, but one only ever sees a small number in popular culture and media. The species in this image is perhaps the one we are shown most frequently – and is the star of Finding Nemo.

Clownfish live in symbiosis with their anemone hosts.

The sea anemone protects the anemonefish from predators, as well as providing food through the scraps left from the anemone's meals and occasional dead anemone tentacles, and functions as a safe nest site.

In turn, the clownfish’s faecal matter provides nutrients to the anemone.

It has also been suggested that the clownfish’s bright coloring might lure small fish to the anemone, which then catches them.

Clownfish are impervious to the poison produced by anemones.

They are photographed so frequently and images of clownfish so common that it’s hard to get an original-looking photograph of them. So it’s nice that this one is so funny.

Reef Manta ray in Hanifaru bay doing a barrel roll

Baa Atoll, Maldives 2015

Occasionally a manta will do an underwater somersault or “barrel roll”. Frequently, mantas perform entire series of barrel rolls -- particularly when there is a concentration of plankton they want to eat and can trap in this way.

Manta bellies, their eyes and cephalic lobes are my favourites! The cephalic lobes, protrusions on either side of the head which can be unfurled, are specific to manta and Mobula rays, and are said to help funnel plankton into their mouths.

I know of nothing more graceful than a manta ray doing a barrel roll.

Manta rays can be identified and catalogued fairly easily (and frequently are) since every individual has a different spot pattern and coloration – a bit like human fingerprints are unique.

The same is true of humpback whales, which are also sometimes catalogued and tracked.

Baa Atoll, Maldives 2015

Occasionally a manta will do an underwater somersault or “barrel roll”. Frequently, mantas perform entire series of barrel rolls -- particularly when there is a concentration of plankton they want to eat and can trap in this way.

Manta bellies, their eyes and cephalic lobes are my favourites! The cephalic lobes, protrusions on either side of the head which can be unfurled, are specific to manta and Mobula rays, and are said to help funnel plankton into their mouths.

I know of nothing more graceful than a manta ray doing a barrel roll.

Manta rays can be identified and catalogued fairly easily (and frequently are) since every individual has a different spot pattern and coloration – a bit like human fingerprints are unique.

The same is true of humpback whales, which are also sometimes catalogued and tracked.

Ghost-like Reef Manta

Hanifaru, Maldives, July 2015

Up to 300 mantas gather in the plankton-rich waters of Hanifaru bay, which isn’t much bigger than a football field, at one time.

They are most numerous around high tide and frequently engage in a behaviour known as “cyclone feeding”.

There are two recognized species of manta ray: the reef manta, which grows to a wingspan of around 4.5 meters and is generally found nearer the reef, and the oceanic manta, which lives in more open water and can reach a wingspan of 7 meters! Scientists are now changing their classification and lumping them into the larger group of Mobula rays. Mantas and Mobulas are sometimes called “devil rays” or devil fish because their cephalic lobes look a little like horns.

Mobulids, like whale sharks and basking sharks, only eat plankton despite their enormous size.

I was lucky to be on this expedition with Tom Peschak of Nat. Geo.

Tom shot the Hanifaru mantas when numbers were highest, in 2008 and 2009 when up 300 mantas could be found in the bay at a time, and when diving was still allowed there. The bay is now protected and patrolled by guards, and only snorkelling is allowed.

Tom also established The Manta Trust, a research and conservation organization, with the trust’s director, Guy Stevens, and co-published a book of his amazing photographs with Guy.

Manta counts were down between 2009 and 2014; but we were lucky to have about 150 mantas in the bay for some swims in 2015.

Manta rays, which are absolutely harmless plankton eaters, are now slaughtered in the thousands for their gill rakers, which purportedly hold medicinal qualities – though of course this is unproven.

Hanifaru, Maldives, July 2015

Up to 300 mantas gather in the plankton-rich waters of Hanifaru bay, which isn’t much bigger than a football field, at one time.

They are most numerous around high tide and frequently engage in a behaviour known as “cyclone feeding”.

There are two recognized species of manta ray: the reef manta, which grows to a wingspan of around 4.5 meters and is generally found nearer the reef, and the oceanic manta, which lives in more open water and can reach a wingspan of 7 meters! Scientists are now changing their classification and lumping them into the larger group of Mobula rays. Mantas and Mobulas are sometimes called “devil rays” or devil fish because their cephalic lobes look a little like horns.

Mobulids, like whale sharks and basking sharks, only eat plankton despite their enormous size.

I was lucky to be on this expedition with Tom Peschak of Nat. Geo.

Tom shot the Hanifaru mantas when numbers were highest, in 2008 and 2009 when up 300 mantas could be found in the bay at a time, and when diving was still allowed there. The bay is now protected and patrolled by guards, and only snorkelling is allowed.

Tom also established The Manta Trust, a research and conservation organization, with the trust’s director, Guy Stevens, and co-published a book of his amazing photographs with Guy.

Manta counts were down between 2009 and 2014; but we were lucky to have about 150 mantas in the bay for some swims in 2015.

Manta rays, which are absolutely harmless plankton eaters, are now slaughtered in the thousands for their gill rakers, which purportedly hold medicinal qualities – though of course this is unproven.

Close-up of a cheek-lined wrasse (Oxycheilinus digramma)

Raja Ampat, August 2015

I took this shot with a macro lens while the fish was in motion and was surprised the image turned out this well.

The fish’s eye kept moving in different directions; it was fun to watch.

Wrasses are beautiful and come in over 600 varieties. They range enormously in colouration and size, with the biggest – the Napoleon Wrasse – measuring up to 2 meters and weighing up to 180 kilos.

Cheek-lined wrasses are native to the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific. They grow to approximately 40 centimetres.

I took this shot with a macro lens while the fish was in motion and was surprised the image turned out this well.

The fish’s eye kept moving in different directions; it was fun to watch.

Wrasses are beautiful and come in over 600 varieties. They range enormously in colouration and size, with the biggest – the Napoleon Wrasse – measuring up to 2 meters and weighing up to 180 kilos.

Cheek-lined wrasses are native to the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific. They grow to approximately 40 centimetres.

This is anchor coral – also known as hammer coral or bubble honeycomb coral – in Raja Ampat, Indonesia, in August 2015

This is my favourite of all my coral photos and a favourite among friends as well.

There was anchor coral in the Philippines when a friend and I were there in 2017 as well.

According to Wikipedia: Anchor coral is widespread throughout the tropical waters of the Indo-West Pacific area from the Maldives to the Solomon Islands with a large presence in Indonesia. It is common in some areas, but it faces several threats that have reduced its overall population. It is overharvested for the aquarium trade. Its coral reef habitat is also degraded and destroyed in many areas.

This is my favourite of all my coral photos and a favourite among friends as well.

There was anchor coral in the Philippines when a friend and I were there in 2017 as well.

According to Wikipedia: Anchor coral is widespread throughout the tropical waters of the Indo-West Pacific area from the Maldives to the Solomon Islands with a large presence in Indonesia. It is common in some areas, but it faces several threats that have reduced its overall population. It is overharvested for the aquarium trade. Its coral reef habitat is also degraded and destroyed in many areas.

A soft coral crab — also known as a candy crab — standing, nearly completely camouflaged, on its habitat in Raja Ampat, West Papua, August 2015

There were actually two crabs on this little piece of coral; but I had a hard time fitting them both in the picture.

It was fantastic seeing these crabs, having never seen them before. Their colours are absolutely stunning.

Candy crab colour depends on that of the host coral. The crabs can be white, pink, yellow or red.

The first pair of legs of this species has small claws.

There were actually two crabs on this little piece of coral; but I had a hard time fitting them both in the picture.

It was fantastic seeing these crabs, having never seen them before. Their colours are absolutely stunning.

Candy crab colour depends on that of the host coral. The crabs can be white, pink, yellow or red.

The first pair of legs of this species has small claws.

One of my very favourite nudibranchs, Nembrotha cristata, in a field of tunicates

Raja Ampat, Indonesia, August 2015

This was one of the most amazing sights… both the nudibranch and the tunicates it feeds on.

I took a large number of shots, many of which look good, of this elegant creature sliding along its habitat, zig-zagging between nutritious obstacles and nourishing itself.

There are many of these slugs in Indonesia and also in the Philippines, where a friend and I went on expedition in 2017.

This species lives at depths between three and twenty meters. Its habitat consists of coral or rock reefs, and it has a lifespan of up to a year.

This was one of the most amazing sights… both the nudibranch and the tunicates it feeds on.

I took a large number of shots, many of which look good, of this elegant creature sliding along its habitat, zig-zagging between nutritious obstacles and nourishing itself.

There are many of these slugs in Indonesia and also in the Philippines, where a friend and I went on expedition in 2017.

This species lives at depths between three and twenty meters. Its habitat consists of coral or rock reefs, and it has a lifespan of up to a year.

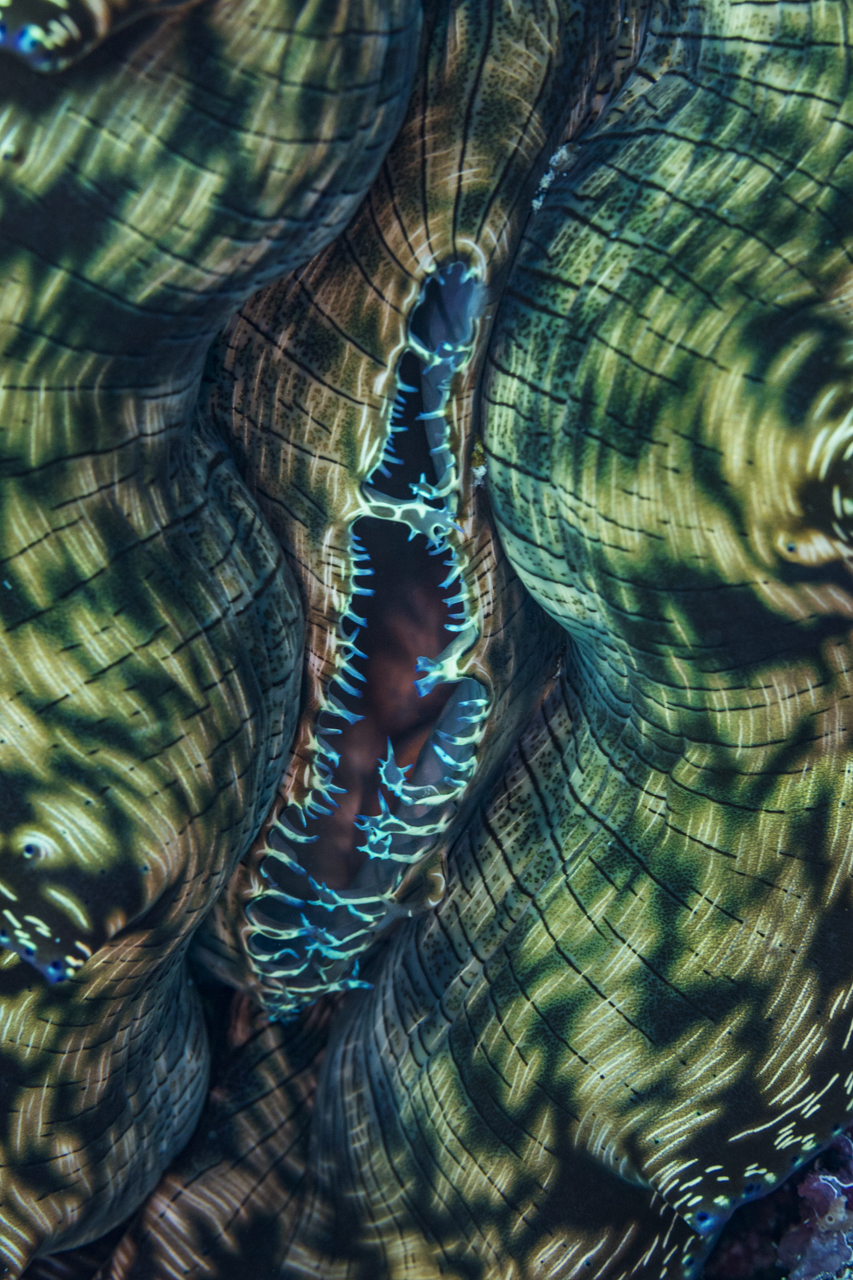

The inhalant siphon of a Giant clam (Tridacna gigas) in Raja Ampat, West Papua, August 2015

One wouldn’t expect a clam to be incredibly beautiful. And yet giant clams really are.

They can live for over 100 years in the wild and weigh 200 kilograms.

Adult T. gigas are the only giant clams unable to close their shells completely. Even when closed, part of the mantle is visible.

Giant clams have eyes! The mantle border is covered in several hundred eyespots.

Generally speaking, clams close at least somewhat as you get closer to them. For a photographer that is very disappointing because they are at their most beautiful when wide open.

One wouldn’t expect a clam to be incredibly beautiful. And yet giant clams really are.

They can live for over 100 years in the wild and weigh 200 kilograms.

Adult T. gigas are the only giant clams unable to close their shells completely. Even when closed, part of the mantle is visible.

Giant clams have eyes! The mantle border is covered in several hundred eyespots.

Generally speaking, clams close at least somewhat as you get closer to them. For a photographer that is very disappointing because they are at their most beautiful when wide open.

A Hypselodoris apolegma

Another one of the most beautiful nudibranchs I know…

Lembeh, Indonesia, in August 2016

The colour of this species is simply breath-taking.

Until the Lembeh trip in 2016 I’d never seen one, and my excitement was tangible when we found several in a week.

Until this specific individual, though, I was incapable, for some reason or other, to take nice images. Much of the seabed in Lembeh is muck – mud and dirt and trash and some sand – and it is all too easy to kick up and ruin photos with.

One of the last days we were told there was one of these nudibranchs at a specific site, and we went there.

I suspect another photographer had kind of cheated and placed the nudibranch in an ideal, easy-to-photograph setting, positioning the animal perfectly. Because when we found it, it was a meter 50 above the bottom sitting on top of the nicest branch of a coral that was itself surrounded by a circle of other tall corals! It was as if a studio had been set up or, at least, a model had been placed in the nicest, largest clearing in the forest.

In that situation it was fairly easy to take this nice picture of a Hypselodoris apolegma down quite deep in North Sulawesi.

Another one of the most beautiful nudibranchs I know…

Lembeh, Indonesia, in August 2016

The colour of this species is simply breath-taking.

Until the Lembeh trip in 2016 I’d never seen one, and my excitement was tangible when we found several in a week.

Until this specific individual, though, I was incapable, for some reason or other, to take nice images. Much of the seabed in Lembeh is muck – mud and dirt and trash and some sand – and it is all too easy to kick up and ruin photos with.

One of the last days we were told there was one of these nudibranchs at a specific site, and we went there.

I suspect another photographer had kind of cheated and placed the nudibranch in an ideal, easy-to-photograph setting, positioning the animal perfectly. Because when we found it, it was a meter 50 above the bottom sitting on top of the nicest branch of a coral that was itself surrounded by a circle of other tall corals! It was as if a studio had been set up or, at least, a model had been placed in the nicest, largest clearing in the forest.

In that situation it was fairly easy to take this nice picture of a Hypselodoris apolegma down quite deep in North Sulawesi.

This is a nudibranch, probably Chromodoris magnifica, we saw and photographed

in the Philippines in May 2017

We found it in the shallows and it was a great model – calm and still!

I would like to tell you that the protrusion on its side is an exhaust pipe, but it is actually a sex organ!

Nudibranchs reproduce side to side and head to toe.

According to Wikipedia, Nudibranchs are hermaphroditic, thus have a set of reproductive organs for both sexes, but they cannot fertilize themselves. Mating usually takes a few minutes and involves a dance-like courtship. Nudibranchs typically deposit their eggs within a gelatinous spiral, which is often described as looking like a ribbon. The number of eggs varies; it can be as few as just 1 or 2 eggs or as many as an estimated 25 million.

We found it in the shallows and it was a great model – calm and still!

I would like to tell you that the protrusion on its side is an exhaust pipe, but it is actually a sex organ!

Nudibranchs reproduce side to side and head to toe.

According to Wikipedia, Nudibranchs are hermaphroditic, thus have a set of reproductive organs for both sexes, but they cannot fertilize themselves. Mating usually takes a few minutes and involves a dance-like courtship. Nudibranchs typically deposit their eggs within a gelatinous spiral, which is often described as looking like a ribbon. The number of eggs varies; it can be as few as just 1 or 2 eggs or as many as an estimated 25 million.

A pigmy seahorse on its coral home 28-30 meters down

In the Philippines in May 2017

They are very hard to photograph since the camera has a hard time focusing on the coral and fish rather than the background, and the wily seahorses turn away or bend downwards most of the time.[1]

The seahorse in this frame was bigger than its companions and looks to me like it might have been pregnant.

This pink species is but one of many. Pigmy seahorses also come in black, yellow and bright red as well as in different shapes. They measure only 1.4 to 2.7 centimetres.

1. Sometimes they bend down AND look away! … The best photos of them, I’m told, are taken by a photographer who places his camera on a tripod about 70 centimeters from these geniuses of camouflage

In the Philippines in May 2017

They are very hard to photograph since the camera has a hard time focusing on the coral and fish rather than the background, and the wily seahorses turn away or bend downwards most of the time.[1]

The seahorse in this frame was bigger than its companions and looks to me like it might have been pregnant.

This pink species is but one of many. Pigmy seahorses also come in black, yellow and bright red as well as in different shapes. They measure only 1.4 to 2.7 centimetres.

1. Sometimes they bend down AND look away! … The best photos of them, I’m told, are taken by a photographer who places his camera on a tripod about 70 centimeters from these geniuses of camouflage

A Pseudoceros bimarginatus flatworm sliding over coral

Apo Island, Dauin, Philippines May 2017

Flatworms are invariably appealing visually – they always please.

They seem rarer than nudibranchs but can be just as colourful.

This particular flatworm was wonderfully positioned on equally beautiful coral.

I was treading water while taking this frame – so worried it wouldn’t turn out well.

At one point the flatworm fell off the plate of coral. I kept shooting and, funnily enough, the pictures of the fall are just as nice as the rest.

Apo Island, Dauin, Philippines May 2017

Flatworms are invariably appealing visually – they always please.

They seem rarer than nudibranchs but can be just as colourful.

This particular flatworm was wonderfully positioned on equally beautiful coral.

I was treading water while taking this frame – so worried it wouldn’t turn out well.

At one point the flatworm fell off the plate of coral. I kept shooting and, funnily enough, the pictures of the fall are just as nice as the rest.

Nembrotha kubaryana — also known as the “variable neon slug” or the “dusky nembrotha” — in the Philippines, May 2017

The same basic black and green colour as its cousin, Nembrotha cristata – another favourite, N. kubaryana has a bright orange face!

My only way to remember the complicated scientific name is to think of KUMBAYA!

Kubaryana, like so many (perhaps all?) other nudibranchs, is poisonous to eat.

Its bright warning colours, like those of poison arrow frogs and monarch butterflies, advertise this fact.

Wikipedia tells us that N. kubaryana uses the toxins in its prey ascidians to defend itself against predators. It stores the ascidian's toxins in its tissues and then releases them in a slimy defensive mucus when alarmed.

Many years ago I saw one of my pet fish, a Comet or “marine betta”, try to eat a sea slug in an aquarium. The fish spat it out 3 times, cementing in me the knowledge that nudibranchs are indeed toxic to fish.

The same basic black and green colour as its cousin, Nembrotha cristata – another favourite, N. kubaryana has a bright orange face!

My only way to remember the complicated scientific name is to think of KUMBAYA!

Kubaryana, like so many (perhaps all?) other nudibranchs, is poisonous to eat.

Its bright warning colours, like those of poison arrow frogs and monarch butterflies, advertise this fact.

Wikipedia tells us that N. kubaryana uses the toxins in its prey ascidians to defend itself against predators. It stores the ascidian's toxins in its tissues and then releases them in a slimy defensive mucus when alarmed.

Many years ago I saw one of my pet fish, a Comet or “marine betta”, try to eat a sea slug in an aquarium. The fish spat it out 3 times, cementing in me the knowledge that nudibranchs are indeed toxic to fish.

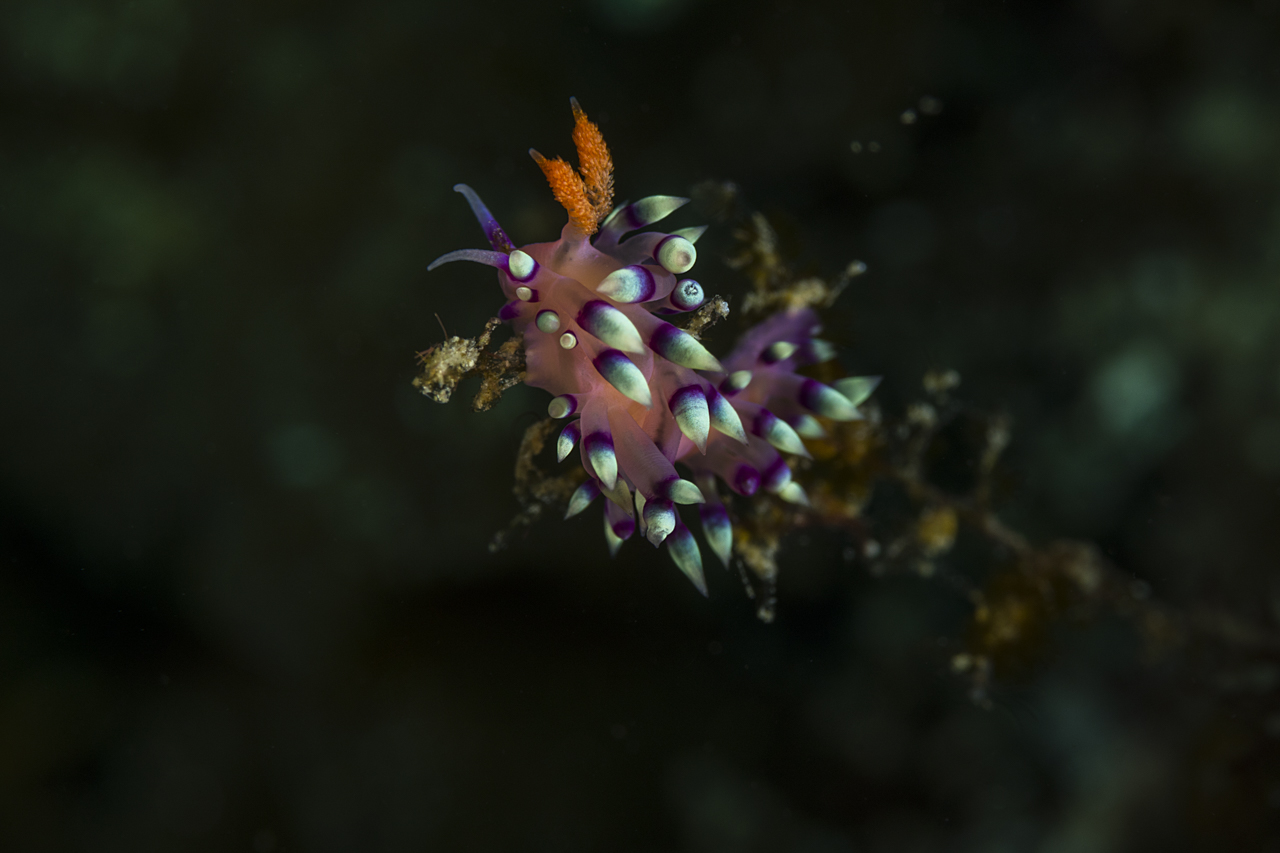

Flabellina exoptata nudibranch (literally translatable as “much desired Flabellina”) at Gato Island, a few miles from Malapascua in the Philippines, May 2017

This was one of the most intricate and interesting nudibranchs I’ve ever seen. Beautiful.

It was balanced on some kind of algal stalk in fairly shallow water and, given its looks and the novelty factor, harder for me to abandon than most things after a shoot. The nudibranch was indeed “much desired”!

While photographing it I was very unsure how much detail would be captured and what the depth of field would be.

This was one of the most intricate and interesting nudibranchs I’ve ever seen. Beautiful.

It was balanced on some kind of algal stalk in fairly shallow water and, given its looks and the novelty factor, harder for me to abandon than most things after a shoot. The nudibranch was indeed “much desired”!

While photographing it I was very unsure how much detail would be captured and what the depth of field would be.

A Spanish dancer nudibranch, which is nocturnal, undulating near Malapascua, Philippines, May 2017

Spanish Dancers are quite large for nudibranchs, growing to a maximum of 60 centimetres long where most nudibranchs don’t exceed 12-14.

They are extremely widespread in the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific, and found as easily off Egypt as the coasts of Hawaii, Indonesia and Japan.

The way they swim and move like a Flamenco dancer is truly magnificent, a sight to behold.

This Spanish Dancer was the first and, thus far, last I ever saw.

Our expert guide found it very easily during a day dive whereas one would usually come across them at night.

Spanish Dancers are quite large for nudibranchs, growing to a maximum of 60 centimetres long where most nudibranchs don’t exceed 12-14.

They are extremely widespread in the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific, and found as easily off Egypt as the coasts of Hawaii, Indonesia and Japan.

The way they swim and move like a Flamenco dancer is truly magnificent, a sight to behold.

This Spanish Dancer was the first and, thus far, last I ever saw.

Our expert guide found it very easily during a day dive whereas one would usually come across them at night.

A Dugong eats voraciously in the sea grass

Marsa Mubarak, Egypt, December 2017

Watching this dugong eat was like witnessing the most powerful hoover suck dirt off a carpet!

It just ate and ate and ate and ate. It ate endlessly during my 45-minute dive with it.

Dugongs feed primarily on seagrass and marine algae, complementing their diet with shellfish and sea squirts, found in seagrass, as well as various invertebrates, including worms.

I couldn’t believe this animal’s appearance! Its nostrils looked like valves, it had beady eyes surrounded by wrinkles, TINY holes for ears and a long, expansive beard.

It would be easy to mistake dugongs for manatees. Both are essentially aquatic cows.

But the primary differences are:

Manatees have horizontal, paddle-shaped tails with only one lobe to move up and down when the animal swims; it’s similar in appearance to that of a beavertail. Dugongs have a fluked tail, meaning it is made up of two separate lobes joined together in the middle.

The snout of a dugong is broad, short, and trunk-like. It faces downward with a slit for a mouth, useful for feeding off the ocean floor. Manatees have a divided upper lip and a shorter snout, which means that they are able to both gather food to eat and feed on plants growing at or near the surface of the water.

As this dugong ate for what seemed like hours, innumerable sand clouds of varying size emanated from its lunch plate. Watching it feed was similar to watching a whirlwind – or a series of adjacent tornadoes.

Marsa Mubarak, Egypt, December 2017

Watching this dugong eat was like witnessing the most powerful hoover suck dirt off a carpet!

It just ate and ate and ate and ate. It ate endlessly during my 45-minute dive with it.

Dugongs feed primarily on seagrass and marine algae, complementing their diet with shellfish and sea squirts, found in seagrass, as well as various invertebrates, including worms.

I couldn’t believe this animal’s appearance! Its nostrils looked like valves, it had beady eyes surrounded by wrinkles, TINY holes for ears and a long, expansive beard.

It would be easy to mistake dugongs for manatees. Both are essentially aquatic cows.

But the primary differences are:

Manatees have horizontal, paddle-shaped tails with only one lobe to move up and down when the animal swims; it’s similar in appearance to that of a beavertail. Dugongs have a fluked tail, meaning it is made up of two separate lobes joined together in the middle.

The snout of a dugong is broad, short, and trunk-like. It faces downward with a slit for a mouth, useful for feeding off the ocean floor. Manatees have a divided upper lip and a shorter snout, which means that they are able to both gather food to eat and feed on plants growing at or near the surface of the water.

As this dugong ate for what seemed like hours, innumerable sand clouds of varying size emanated from its lunch plate. Watching it feed was similar to watching a whirlwind – or a series of adjacent tornadoes.

The Marsa Mubarak Dugong descends with all his remora acolytes after taking a breath at the surface

Egypt, December 2017

Despite the dugong moving extremely slowly most of the time and allowing me to come within 3 or 4 meters of him, I ran through my tank much faster than usual and was hyperventilating, my breathing out control, for the better part of the dive.

There was a surprisingly strong current, my friends and I kept having to adjust our buoyancy for the animal’s ascents and descents, and this creature, at the time the object of my affection, took us for an unexpected and extended tour around much of the gigantic bay he lives in!

It was a surprisingly difficult shoot for an experience with an animal you could outswim ninety percent of the time; but at least the frames I captured are beautiful.

Egypt, December 2017

Despite the dugong moving extremely slowly most of the time and allowing me to come within 3 or 4 meters of him, I ran through my tank much faster than usual and was hyperventilating, my breathing out control, for the better part of the dive.

There was a surprisingly strong current, my friends and I kept having to adjust our buoyancy for the animal’s ascents and descents, and this creature, at the time the object of my affection, took us for an unexpected and extended tour around much of the gigantic bay he lives in!

It was a surprisingly difficult shoot for an experience with an animal you could outswim ninety percent of the time; but at least the frames I captured are beautiful.

The famous young male Dugong at Marsa Mubarak goes upright after a long seagrass snack!

It seemed for a few seconds like he was trying to shake off his Remoras as well.

Egypt, December 2017

This is one of the frames in my portfolio that appeals to people the most. And the first FONASSOCIATION Instagram post to garner more than 400 likes, accumulating over 550 of them.

We were very lucky, Simo, Jim and I, to get 2 dives completely alone with this character – after a first dive during which he was surrounded or, rather, crowded out by about 8 snorkelers, 4 other divers and us.

This animal was one of the most interesting I have ever encountered.

So fat, so bizarre, so original, so hungry, and so slow.

Unfortunately this marine mammal may be a victim of his own success – drawing in more tourists than might otherwise be desirable and, in so doing, rendering his lifestyle both less appealing and less natural/wild than it might otherwise be.

It’s hard to believe that the mermaid legend was born from sea cows – either manatees or dugongs.

History books specify that the Spanish sailors who found the New World had not seen any women for many months.

By the time they might have come across a manatee – and imagined it a pretty girl with a fish tail!

It seemed for a few seconds like he was trying to shake off his Remoras as well.

Egypt, December 2017

This is one of the frames in my portfolio that appeals to people the most. And the first FONASSOCIATION Instagram post to garner more than 400 likes, accumulating over 550 of them.

We were very lucky, Simo, Jim and I, to get 2 dives completely alone with this character – after a first dive during which he was surrounded or, rather, crowded out by about 8 snorkelers, 4 other divers and us.

This animal was one of the most interesting I have ever encountered.

So fat, so bizarre, so original, so hungry, and so slow.

Unfortunately this marine mammal may be a victim of his own success – drawing in more tourists than might otherwise be desirable and, in so doing, rendering his lifestyle both less appealing and less natural/wild than it might otherwise be.

It’s hard to believe that the mermaid legend was born from sea cows – either manatees or dugongs.

History books specify that the Spanish sailors who found the New World had not seen any women for many months.

By the time they might have come across a manatee – and imagined it a pretty girl with a fish tail!