The fragile biodiversity of Indonesia

By Prince Hussain Aga Khan

Aga Khan Museum & Aga Khan Park

77 Wynford Drive

Toronto, ON M3C 1K1

September 23, 2023 – March 31, 2024

Since his childhood, Prince Hussain Aga Khan has been fascinated by the beauty and increasing fragility of ocean life. Through the art of wildlife photography, he has dedicated his life to raising awareness of underwater worlds that are breathtaking in their kaleidoscopic colours and diversity. They are now under imminent threat. In less than 30 years’ time there will be more plastic than fish (by mass) in our oceans.

For this exhibition, Prince Hussain has collected photographs taken between 2011 and 2023 in Indonesian waters, some of the most biodiverse underwater places on the planet. These photographs give us much to think about and reflect Prince Hussain’s commitment to encourage global efforts to conserve the world’s animal species and ecosystems.

A Clark’s anemonefish, a.k.a. yellowtail clownfish, hovers over its home anemone.

The symbiosis between clownfish and anemones is one of the more interesting phenomena in nature.

The clownfish benefits from the anemone’s protection whilst the anemone, whose tentacles sting practically every other kind of fish (damselfish notwithstanding), benefits from extra food and nutrients provided by the clownfish.

It’s fairly common to see an anemone without any clownfish; but very rare to see a clownfish far from any anemone.

And many aquarists will tell you that clownfish frequently die if their anemone dies – and very rarely alternate between anemones. Most clowns seem entirely lost if their anemone dies and take time before picking another anemone – if they ever actually do so.

Interestingly – and although we see very few in media and aquaria – there are nearly 30 known species of clownfish!

Indonesia, August 2011

This was my first - and one of my last - giant frogfish sitting on very large sponges somewhere near Komodo on a trip with my best friend.

Indonesia, August 2011

Had the guide not pointed out this mysterious and wonderfully camouflaged animal, I never would have noticed it.

Frogfish are masters of disguise! They blend into their environment nearly perfectly.

Coming in many colours, including black, white, yellow, orange and even striped[1], it’s always wonderful to bump into frogfish – and see them sitting on their pectoral fins, which have evolved into something like kickstands!

Whilst giant frogfish can reach 38 cm in length, some frogfish species only reach 2.5 cm!

There are approximately 60 species, including the beautiful clown frogfish and the unimaginable hairy frogfish – which literally looks covered in hair.[2]

And deep-sea anglerfish, whose luminous lures that dangle in front of their faces attract prey in the dark, are part of the same family of fish.

[1] Many frogfishes can change their colour. The light colours are generally yellows or yellow-browns, while the darker are green, black, or dark red. They usually appear with the lighter colour, but the change can last from a few days to several weeks. What triggers the change is unknown.

[2] A hairy frogfish also appears in this exhibition.

A Halimeda ghost pipefish stands out from its environment for once.

Lembeh, Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 2011

Pipefish are related to seahorses and come in multiple forms.

Most pipefish are tubular, very thin and quite colourful – a little like a beautiful straw with a head on one end and a tail on the other.

Ghost pipefish, which come in 5-7 species depending on the source, “are no longer than 17 centimetres (6.7 in), float near motionlessly, with the mouth facing downwards, around a background that makes them nearly impossible to see. They feed on tiny crustaceans, sucked inside through their long snout. They live in open waters except during breeding, when they find a coral reef or muddy bottom, changing color and shape to minimize visibility.”

Indeed, the pipefish in this image was nearly indistinguishable from the Halimeda algae next to which it hovered. Indistinguishable, that is, until my guide gently directed it off to the side.

The Halimeda ghost pipe is reportedly the smallest species, growing only to 6.5 centimetres.

Other recognized ghost pipefish species include the robust which, as its name implies, is thicker than others; the ornate, which is spiky and comes in many colours; the long-tailed ghost pipefish; the roughsnout ghost pipefish and; the delicate ghost pipefish.

Hairy Frogfish!

Lembeh, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 2011

Can you believe this is a fish?

I couldn’t…

It literally has what look like hairs growing on it!

This was a fairly small animal. Extremely intricate and absolutely fascinating.

My buddy Oli and I saw a much larger and rubbery-looking black hairy frogfish in the Philippines a few years later – evidence of diversity of species, as well as size and color within families of animals.

Frogfish spend practically their entire lives sitting on the seafloor, against organic structures like sponges or camouflaged on the reef. They are clumsy swimmers and don’t change location very often or fast. Hence, if a guide or diver sees one somewhere on the reef or sand one day, it is very likely others can find them there the next day and for many days (even months in some cases) after. They are very hard to identify to the untrained eye. And magnificent examples of anatomical evolution.

Probably a raggy scorpionfish confident in his disguise, ideally set up to be framed.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

Many people, certainly in Europe, would call this a ‘stonefish’ and not a scorpionfish. But anywhere from Lembeh to Bunaken, Raja Ampat or the Philippines, they’re referred to as scorpionfish.

There are literally dozens of species of scorpionfish in the Coral Triangle.

Supremely disguised and often ideally positioned like this one, you often swim past one, totally unaware of its presence until

your guide points it out. Scorpionfish all have venomous spines that can give nasty stings and cause massive swelling and pain.

Luckily, most divers will never suffer this pain. Scorpions stay hidden, nestled in the reef, and only hurt you as a defence mechanism.

It would be lovely to tell you what this is – if only I knew!

Certainly an anemone – and one with a clownfish, which would have been my main focus, living in it.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

This is the face of a very large cuttlefish, waving two of its tentacles around in front of it.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

We had a huge pair of cuttlefish at the end of a dive, my friends Maria, Zeph and me.

Whilst I thought they were giant cuttlefish, it seems that species only exists around southern Australia.

Not shy at all, these cephalopods must have allowed me close for five minutes or more as I moved all around them to capture different angles.

It always comes as a surprise (a very welcome one!) when wild animals let you close and appear to trust you.

I’m not entirely sure what this animal was doing – or trying to tell me – as it waved its tentacles about as high as its head and in different directions.

Octopus and cuttlefish, highly intelligent (including at problem solving and in feeding techniques) and versatile, are mollusks – and so related to slugs and snails!

They can not only change color at will, mainly in order to blend in with their surroundings, but also even change the TEXTURE of their skin to improve their camouflage.

They also squirt ink when threatened or being chased by predators – leaving the predator confused, its vision hindered, while giving the cephalopod some time to escape.

And cephalopods are BRILLIANT escape artists and movers. Octopi can slip into bottles and even reside in them (I’ve seen this in Lembeh, Indonesia), escape from closed aquaria and even open up and navigate through drains! (The latter is precisely how Inky the octopus escaped from a public aquarium in New Zealand)

Once you’ve witnessed the intelligence and relative beauty of cephalopods and watched how marvelously they move – using a siphon – and mimic their surroundings, it becomes very hard to even imagine eating them — or pasta covered in their ink.

Flatworms about to fight or mate. Or fight TO mate!

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

I believe this species is Maritigrella fuscopunctata (apparently known as the “punctuated flatworm”).

This was an incredible moment to witness, and I could hardly believe my eyes.

Two flat creatures raised on their back ends to face each other.

With a little research you’d find out that in order for flatworms to reproduce two males fight and aim to stab each other. The (stabbed) individual who lost the fight becomes female and produces offspring.

Some species of flatworm do, however, practice a less confrontational method of breeding.

“Many hermaphroditic species mutually inseminate, rather than compete.”

Extremely colourful – and blind – just like nudibranchs, I’m not entirely sure whether flatworms are also poisonous like nudibranchs, whose bright “warning colors” advertise their toxicity and ward predators away.

Pygmy seahorse (H. bargibanti) holding onto its gorgonian base.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

Pygmy seahorses are TINY – no bigger than one of your nails – and extremely camera shy.

They seem to twist and turn and bend and slouch in every and any direction it takes to avoid the camera.

Stunning creatures, they come in a variety of colours including pink, red, and pale yellow.

There are 9 recognized species of pygmy seahorse including this one, Denise’s, Coleman’s and the Japanese pygmy seahorse. There are at least 4 other dwarf species of seahorse; but for anatomical reasons they are not considered true pygmies.

All pygmy seahorse species live in Southeast Asia.

These animals blend marvellously into their habitat. They are so small and the gorgonian branches so thin and homogenous that if you take your eyes off the animals for mere seconds it can be very hard to find them again.

Photographically speaking, one difficulty is that the camera has a very hard time focusing on the animals – and even on the gorgonians they dwell on. Instead, the camera keeps trying to find a focal point behind the coral.

Another difficulty is that many or most of the gorgonians the seahorses dwell on jut out laterally from the reef wall quite high off the seabed. Hence you are treading water, not standing or kneeling, nearly every time you shoot pygmy seahorses.

In fact, I’ve only had the luxury of kneeling in front of pygmy seahorses twice out of perhaps twelve sightings.

See Nemo in the comfort of his home!

Amphiprion ocellaris

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

One of my favourite species—along with Amphiprion perideraion and Amphiprion akallopisos— Amphiprion ocellaris is probably the most frequently shown in the media and bought for aquaria.

Clownfish are extremely protective of their babies and families! In spite of their small size, they will often swim right out of their host anemone—a metre or more—and try to bite you. At least scare you away. ‘You shall not pass!’

Clownfish are closely related to damselfish, which are also very common in the aquarium trade and frequently share anemones with them.

The nicest thing to see with these is the babies. Both clownfish and damselfish babies are adorable as they swim around in the anemone, interacting with their loving parents and each other. Clownfish don’t grow big anyway—no more than 11 centimetres—but seeing tiny ones in their safe havens never fails to leave an impression.

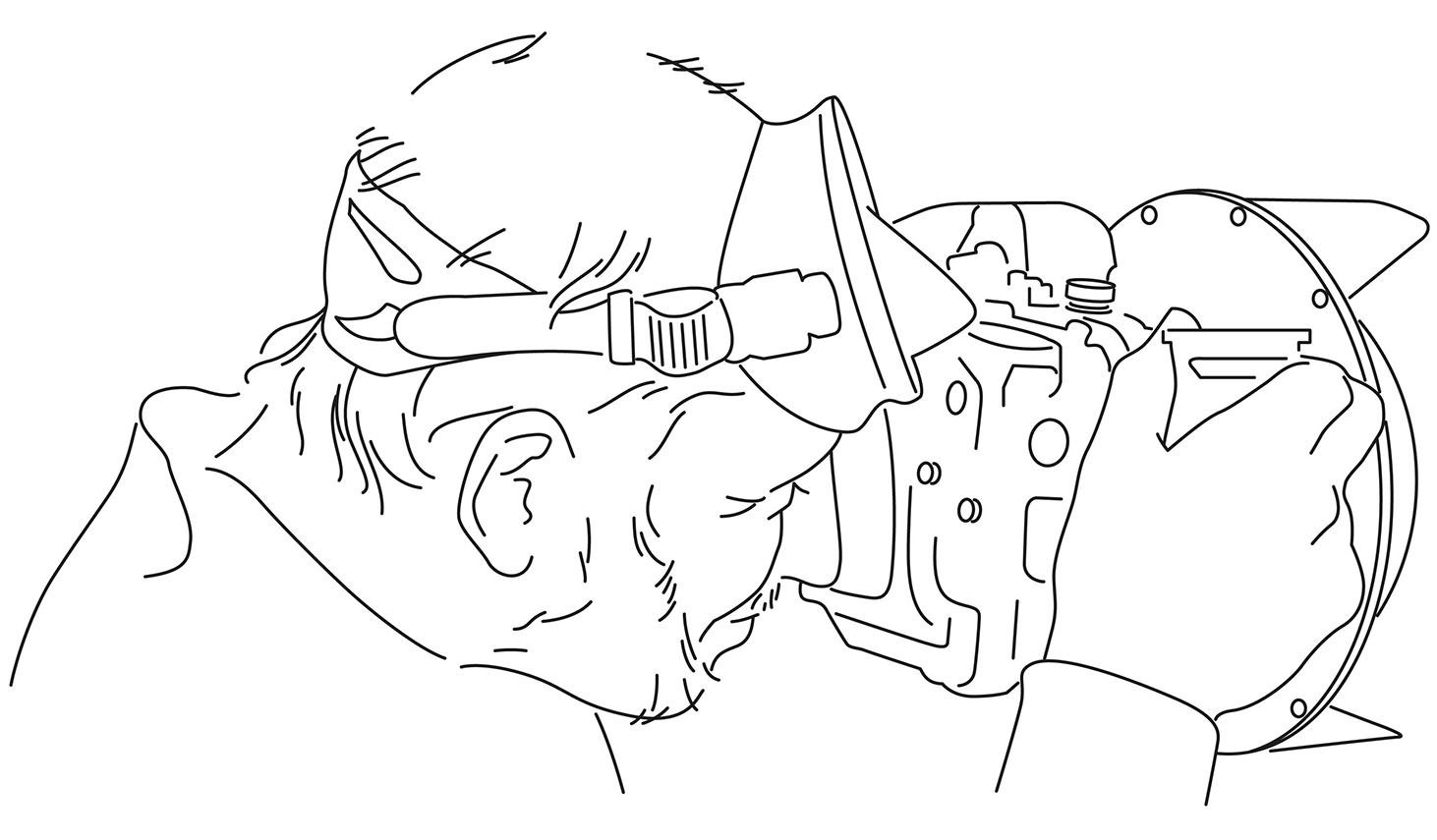

The inhalant siphon of a giant clam (Tridacna gigas).

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

One wouldn’t expect a clam to be incredibly beautiful. And yet giant clams really are.

They can live for over 100 years in the wild and weigh 200 kilograms.

Adult Tridacna gigas are the only giant clams unable to close their shells completely. Even when closed, part of the mantle is visible.

Giant clams also have eyes! The mantle border is covered in several hundred eyespots.

Clams always close a little as you get closer to them. For a photographer, it's very disappointing because they are at their most beautiful when wide open.

But no matter how slowly or cautiously you approach a clam it invariably retracts once it has sensed (or seen!) you.

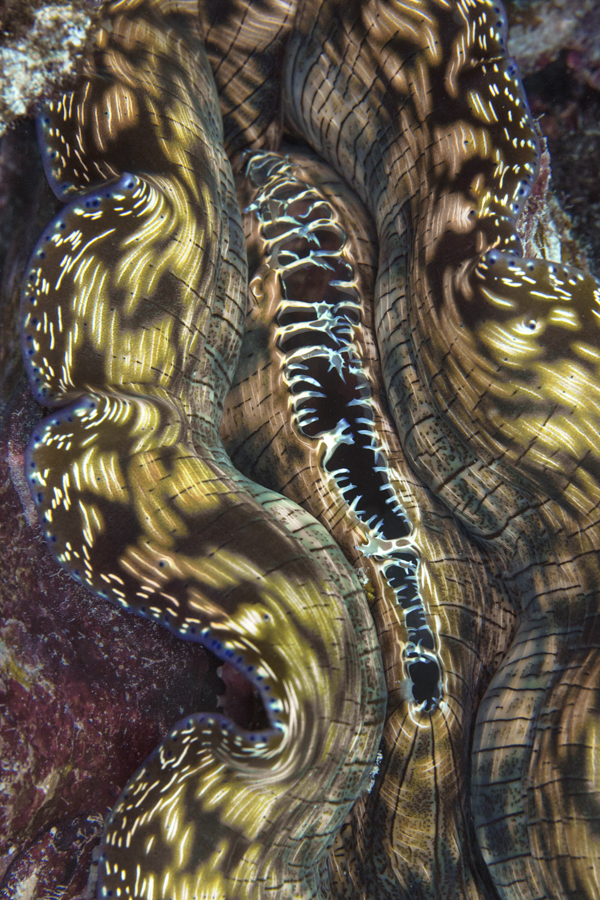

A SMILY FACE of soft coral!

Maybe half a smily face — seen unexpectedly yet memorably on a beautiful and biodiverse reef.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

Beautiful ribboned sweetlips among hundreds of glass fish at a small but famous overhang.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, August 2015

The sweetlips are beautiful and in a tightknit group; the glass fish fascinating and numerous—forming an ever-shifting shape. Occasionally their formation is like a perfect wall – with not a single fish pointing forwards or even slightly behind the others in a straight, vertical line.

The guides in Raja all know this place and take divers there all the time.

There couldn’t possibly be two places like it -- and you couldn’t possibly forget it.

We were taken there by our guide Lius in one quick and easy journey to this specific part of the reef.

Guides know all the popular resident animals and where they live in places like Raja Ampat or Lembeh. Just as you would know where your favourite flower is in your garden or which tree your resident squirrel lives in, they know where to take you for sweetlips inhabiting an overhang, pygmy seahorses on a gorgonian, a clown frogfish on the bottom or candy crabs on soft corals.

Sometimes, a dive site is named after its residents. For example, a nudibranch stronghold in Lembeh is known as Nudi Retreat.

I shall never forget this place or these fish and hope to visit them again someday.

There are thirty-one species of sweetlips and every one I know is intriguing and colourful.

Wikipedia tells us, ‘These fish have big, fleshy lips and tend to live on coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific in small groups or pairs. They will often associate with other fishes of similar species; several species of sweetlips sometimes swim together. They are usually seen in clusters in nooks and crannies or under overhangs. At nightfall, they venture from their shelters to seek out their bottom-dwelling invertebrate prey, such as bristleworms, shrimps and small crabs.’

‘Lone star!’

A batfish cruises past a large school of black snapper.

Raja Ampat, Indonesia, August 2015

Phyllodesmium longicirrum, an aeolid nudibranch whose common name is ‘solar-powered nudibranch’.

Lembeh, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 2016

I really thought the guide in Lembeh was joking when he called this thing a ‘solar-powered nudibranch’, but that is an official name! Some of these were so big that when I first swam past them, I thought they might actually be chunks of coral. These nudibranchs are capable of photosynthesis and, if I remember correctly, the dark patches on the slug are the food production areas.

A Glossodoris cincta nudibranch

Lembeh, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 2016

These nudibranchs seemed to me more common than other species in the area.

I love how this animal’s back looks a little like a galaxy or a star-spangled sky…

Peacock mantis shrimp

Lembeh, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 2016

Their compound eyes, on stalks and some of the most complex in the animal kingdom, are ridiculously bizarre and move in incredible ways, frequently independently of one another.

Whilst humans possess only three types of photoreceptor cells in their eyes, mantis shrimp have between 12 and 16 types!

Occasionally you see females clutching an enormous number of eggs (their own) between what look like their arms.

The paddles at their sides can hit with more speed and proportional force than any other animal.

They can break aquarium glass and camera dome ports with a whack!

Depending on their claw type, mantis shrimp are either “smashers” or “spearers”.

Smashers “possess a much more developed club and a more rudimentary spear (which is nevertheless quite sharp and still used in fights between their own kind); the club is used to bludgeon and smash their meals apart. The inner aspect of the terminal portion of the appendage can also possess a sharp edge, used to cut prey while the mantis shrimp swims.”

Whilst they live in burrows, they sometimes sort of rush out towards you in what seems like an intimidation tactic! But they retreat rather fast.

There are apparently about 520 species of mantis shrimp. My dive buddies and I have seen maybe 8 species…

Giant mantis shrimp are much larger than peacocks and others.

Ornate Ghost pipefish.

Lembeh, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, August 2016

Pipefish are related to seahorses and come in a variety of beautiful designs and colours. Ghost pipefish are amazing! Some of the strangest, least imaginable things you could ever see. They swim around with their head – a long tubular snout with an eye just before the gills behind it – pointing to the bottom, and their tail – a bit like a fan – pointing towards the surface.

To the untrained eye ghost pipes are virtually invisible. They look so much like their hosts or habitats.

There are only six recognised species of ghost pipefish (Solenostomus), but all are masters of camouflage.

Species include this spiky one, the Ornate ghost pipefish. This is the species my friends and I have seen the most in Lembeh. There are at least three colours of ornate ghost pipes we have seen – red, yellow and black. But more colour forms exist. Ornate ghost pipes spend their time hovering within or against crinoids and are nearly indistinguishable from them.

Another species is the Robust ghost pipefish, which is markedly thicker and slightly less decorative than the rest. These look like thick chunks of seaweed floating around in the current. They’re not particularly colourful or intricate – unlike the ornates.

Halimeda ghost pipefish are another species, and they blend perfectly with the Halimeda algae they live around.

The other three recognised species, which I have never seen, are the Delicate, the Long-tailed and the Roughsnout ghost pipefish.

Whilst it may not be an official species I once saw a pair of Hairy ghost pipefish in the Philippines, which were much bigger than any others I’ve seen and literally looked like they were covered in algae or fluff. They were swimming around a ball of similar-looking plant matter.

Ghost pipes feed on tiny crustaceans they suck up through their long snouts. Just about the only time you see them move, other than slowly floating about and mimicking their host or habitat, is when they open that snout for the briefest moment to eat. Most of the time you see couples of ghost pipes, but occasionally you will see a solitary one. In nearly every case, unless the fish are already a certain distance from their background or host, your dive guide will have to gently coax them out/away in order for you to see them.

A number of two-spot red snapper and Chromis (damselfish) suspended among and above some beautiful hard coral fairly close to Misool Resort.

Misool, Indonesia, January 2023

This was an incredible sight (and site!) and we had to ensure not to break any coral while photographing it – not always the easiest of tasks.

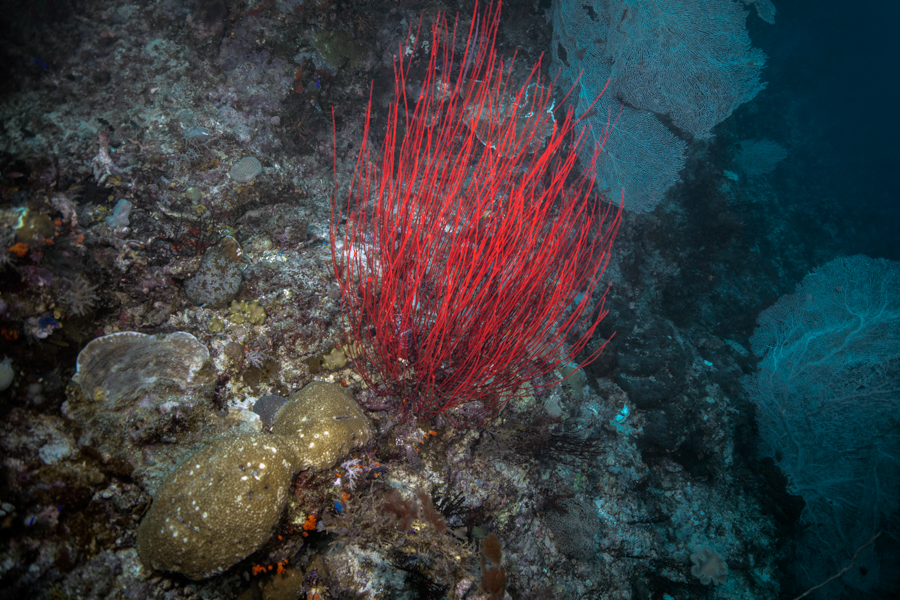

Some beautifully colored and shaped red whip coral on the reef at Misool.

Misool, Raja Ampat, January 2023

The incredible strands are reminiscent of very tall, thick grass.

Healthy coral is one of the most phenomenal things to see. And the diversity

Of coral species, hard and soft, is truly staggering.

At Misool Resort, in the biodiversity hotspot of the Coral Triangle, they have counted approximately 600 species of coral and 2,200 species of fish!

Truly one of the most stunning and colorful sea fans I have ever been privileged to come across.

Unbelievable beauty and extreme elegance…

Wakatobi, Indonesia, January 2023

Incredible spirals of Turbinaria reniformis coral at a site at Wakatobi.

Indonesia, January 2023

The complete structure and others there were massive – so big and healthy it was hard to believe as you swam over and around them.

These beautiful corals immediately became our models and we spent a long time photographing them every time we dove that site.

One normally wouldn’t compare much to Raja Ampat, which is the pinnacle of marine biodiversity and ecosystem health; but the coral at Wakatobi is by far the best I’ve ever seen.

Beautiful, grandiose structures, outlandish colors, dainty lattices, amazing variety…

A pink skunk clownfish peeks out of its spectacular anemone home on our penultimate dive at Wakatobi.

These colors were beyond vibrant – one of the reasons we returned to this site.

Indonesia, January 2023

An orangutan crab rests upon its bubble anemone home on the wall at Wakatobi.

I’ve never seen an orangutan crab NOT on a bubble anemone in fact.

One or two websites claim that the crab actually creates the beautiful base upon which it sits; but I’m not at all certain of the veracity of this information.

These crabs are very small. You could probably fit three or four in your hand without them even touching each other.

They’re also quite hard to photograph even with a macro lens: difficult to get every hair, as well as both of their claws, in focus.

An extra difficulty in this case was that we were treading water the whole time we were photographing this creature – in order not to break any of the coral around it.

These are some of the most bizarre animals you could ever encounter underwater.

Indonesia, January 2023

Multiple generations of pink skunk clownfish dwell in an anemone that was, at that moment, partially closed.

Wakatobi, Indonesia, January 2023

Magical reef manta at Eagle Rock, one of the more famous manta sites in Raja.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, March 2023

Manta rays are much more common – reliable in their presence – in some areas than others. Many dive destinations include specific sites for them.

They are, in many people’s opinion, the most graceful and elegant creatures in the world.

Peaceful and mysterious, they are often quite curious.

Mantas will frequently come right up to divers to check them out. Sometimes they even hover above divers to get tickled by their bubbles!

Guides and instructors nearly always tell you to sit and wait rather than swim after them, which can scare them away.

If you’re patient it’s very likely that a ray will come right up to you.

Mantas can be extremely playful and it's quite possible one will let you swim with it, eye to eye, for minutes at a time.

But of course every animal is different and what one animal allows many others might not.

Different mantas have played with or shown off for me in Mexico, Polynesia and off the coast of Ecuador.

The manta in this image had just circled around the rock they glide down to and looked right at me before taking off towards somewhere above me.

Stunning wall of glassfish under an overhang that was also inhabited by a wonderful wobbegong.

Whilst the glassfish were generally grouped and in formations (as is always the case), the variance in topography and light made for very mixed photographic results.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, March 2023

Amphiprion ocellaris

One of the most common clownfish in the region and many people’s favorite…

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, March 2023

A ribboned sweetlip behind a gorgonian and above a sponge.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, March 2023

The famous ribboned sweetlips of Cape Kri — in a ball and surrounded by glass fish!

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, March 2023

Depending on the current at Cape Kri, the sweetlips are either in larger numbers around and in-between two large rock formations in slightly deeper water (maybe 32 metres) or, as in this photograph, in smaller but still significant numbers around one large rock or coral head in only slightly shallower water.

We returned to this site twice because of how special it is and how photogenic the sweetlips are.

What you don’t see in this image is a once common, now critically endangered, very large Napoleon wrasse, which was lazing about among the sweetlips and close to the sand.

Because the site is quite deep you can’t stay with the sweetlips for very long – and I was unable to photograph the more amazing sight of many more sweetlips spread out over the sand in an area maybe 25 by 30 meters around the two rocks at the deeper spot the day before. Very disappointing because it was one of the most impressive things my buddy Oli and I have ever seen.

Cape Kri is a very popular dive site and we were lucky to be alone with the sweetlips two times out of three.

This image was taken by my close friend and photographic assistant Olivier Clément.

Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia, March 2023

One of the most horrid sights imaginable…

Close to Misool, the southernmost island making up Raja Ampat, we ran into what were basically corridors of plastic pollution/trash at the surface.

It was as if an entire expanse of the sea were divided into sectors by garbage paths.

The idea that one of the most pristine parts of the world’s oceans – and one of the two most biodiverse places underwater on the planet – is becoming invaded by plastic is beyond horrific. And a reminder that many (or even most) of our environmental problems are global, not just at the local scale.

Guillaume, our guide on the expedition, said that the plastic here is the result of currents originating from the South Pacific garbage patch (a.k.a. “Plastic Island(s)” or the “South Pacific Gyre”, depending on who is speaking) – whereas other people mentioned local mismanagement/poor practices to us.

Sadly, Indonesia is one of the world’s top plastic polluters and faces a “plastic waste emergency”.