I’ve always loved, been fascinated by, sharks. From the earliest age and at the first view of them on tv I wanted to know more about them, see them in real life and understand what they did.

I’m quite sure that, were it not for films like JAWS, Deep Blue Sea and the Shallows, we wouldn’t be anywhere near as afraid of sharks as we are.

I’m also convinced that the younger you are to experience something considered dangerous, the more likely you are to be ok with it and brave. I was never really afraid of snakes because my siblings and I first handled one with an adult in Sardinia when I was about 9.

With sharks… it seems lucky to me that the first one, a little reef shark, swam by me when I was 14 or 15.

The whole idea that sharks will most likely attack you if they see you in the water is as much of a fallacy as the idea that if you jump into the water with a pod of wild dolphins they will want to play with you.

If one includes species that have only been seen dead or found a small number of times (Megamouth etc.), over 350 different species of shark have been identified. And of those a huge number are sharks you would never see swimming, that live at night, very deep, under ledges or on the ocean floor. Many species of sharks, which are related to rays — also cartilaginous fishes, look nothing like what you imagine a shark looks like. Some are flattened, some guitar-shaped, some look like carpets… Some just look like normal fish with big eyes, strange heads or tails. Shark size ranges from 20 centimeters for the dwarf lantern shark to 18.8 meters for the whale shark – the biggest fish in the sea. The vast majority of shark species have never been known to attack anybody. And humans are decimating sharks at an unprecedented and horrifying rate. We kill 100 to 273 million sharks a year, including those taken for their fins, which are cut off when they’re alive (the sharks are then thrown back into the water, unable to swim and left to die), those entangled in nets and taken by mistake as by-catch. And yet sharks kill only 6 to 8 people a year around the world. So sharks are killing us at perhaps 0.000000029304029 to 0.00000006 the rate we kill them. It is said that overall shark numbers have declined by ninety percent over the past few decades.

It has been an incredible privilege over the years to see perhaps 12 species of sharks, including the zebra, tiger, whale, thresher shark, wobbegong (which looks like a carpet!), the very rare and endangered oceanic white tip, and two species of hammerhead.

Only about 12 times – split between perhaps 4 individual animals – have I felt a shark liked me too much or might, had I been unfortunate, hurt me. Each time I was in the water with dead fish and blood to attract them.

About three times a year, I take friends whose diving skills are unquestionable to see tiger sharks, great hammerheads, and oceanic white tips in the Bahamas.

One pretty much has to draw sharks in with food to see them. Of course you might see a shark at random on a dive, and it might be the species you’re most interested in. But if you want good photographs, including close-ups, and to really get to know a species you need to travel to where it’s commonly seen, go to the site experts and professionals visit, and, usually, throw fish and blood in the water to bring the sharks in.

This chumming is such a common practice in some places, and works so well, that the feeders and guests see the animals nearly every time[1]. In fact, some sharks attend these free meals so often that the feeders can easily identify/recognize them. Emma, for instance, is one of the more famous sharks at Tiger Beach in Grand Bahama.

For tiger sharks we have to travel about an hour and a half to Tiger Beach, in Grand Bahama, which isn’t a beach at all. It’s a sandy bottom - with the odd bit of coral reef here and there - in the same area where we find the spotted dolphins I go and see with the Wild Dolphin Project every summer. Someone told me that it was people searching the area for dolphins who first noticed there are lots of tiger sharks there.

At Tiger Beach the first thing you see when you anchor is a large number of lemon sharks, eager to eat the chum from the shark boats, waiting at the surface. They form a sort of moving, ever-changing circle of diners and eat nearly everything we throw in – while we are actually chumming for tigers. There are more lemon sharks at the bottom, and frequently Caribbean Reef Sharks, too. The Tiger Sharks nearly always come at some point. They’re much bigger, and more colorful, than the other sharks — with their beautiful markings and squarish faces. The least tiger sharks I’ve ever seen on a dive there is 1, the highest number 5. We once waited more than an hour at the surface, chumming over the side of the boat for what seemed like forever, for a tiger to come only at the end of the dive… two hours after we started feeding. Other times a nearby boat already had a tiger when we arrived ... or the shark(s) came very soon after we anchored.

The feeders sometimes stroke the noses of the tiger sharks, and the eyes roll white – to protect from possible damage[2], or push their heads down towards the sand to avoid teeth. Sometimes they keep one hand on the nose and redirect the shark with the other hand on the body, pushing the animal forward or sideways. We’re given plastic sticks, white and about a meter long, to ward sharks off if they come too close, and we’re told never to take our eyes off a tiger shark when it comes near –– to keep looking at them even once they’ve swum past us in case they choose to turn around and approach us from behind.[3] Overall, though, and over the course of 8 or more dives at Tiger Beach, friends and I have rarely been scared of a tiger shark: we haven’t had cause to be.

The original feeder we used, who must have done thousands of shark dives, would joke that he had “two chances” with tiger sharks: they bump something first before they bite it.

Cameras are very good buffers, particularly when strobes are attached, making the rig bigger, and can be used to push sharks away.

The tiger sharks, while impressive — and some of them very big (Emma is 14 feet long!), seem to move slowly... nearly as if it’s a task to carry their heavy bodies around. And one could almost argue that some of the ones at Tiger Beach are unnaturally habituated to people.

There are literally thousands of photos of Tiger Beach, and the tiger (and, occasionally, great hammerhead) sharks there, on Instagram and the Internet. Emma the tiger shark in particular.

For the Great Hammerheads we go to Bimini, which is also prime territory for the Atlantic Spotted Dolphins.

And just like with the tiger sharks, it’s very shallow water, the feeder stands on the sand next to the bait box, and the divers sit in a line or semicircle some distance away, opposite the feeder.

The nicer feeders frequently take fish out of the covered bait box (a crate) and give them to the sharks. The slightly less nice or novice feeders keep the bait box closed nearly all the time, which keeps the sharks around since they still smell the fish and blood in the water; but keeps them unjustly hungry, too!

Where there are lots of lemon sharks and some reef sharks on the tiger dives, there are lots of lazy nurse sharks on the sand, hoping for food and often close to the bait box, on the hammerhead dives. On the hammerhead dives we also frequently see bull sharks, which are considered more dangerous, and are quite girthy.

Great hammerheads are HUGE — reaching up to 6 meters in length , and their dorsal fins are very tall.

They are in the books as some of the more dangerous sharks; but I have never seen one look threatening or come up close on a dive. The last feeders we had said the same thing: they’re not in the least interested in us and, if anything, they avoid us. They come in for the food, barely look at the feeder (“shark wrangler”) or divers, turn away immediately, and then come back for more.

Sometimes they dip their bodies to one side, looking almost diagonal when you see them swim.

The nurse sharks are basically puppies. They sit on the ground, they mill around, they look and are harmless. They just want their food.

Despite their enormous size, and awkward shape, the hammerheads can turn on a dime. You should see the speed with which they swivel over the bait box after taking a fish and before heading away again. One of the theories about the hammer used to be that moving their heads side to side helped them swim faster. Called the cephalofoil, the hammer is apparently occasionally used to hit stingrays and skates, favorite foods, from above. It also serves as a hydrofoil that allows the sharks to turn quickly. Apparently the cephalofoil is also used to detect prey and can pick up the electrical signatures of buried stingrays.

One nice thing about the hammer dives is that once we’ve arrived at the airport and got on the boat, the shark-feeding spot is only a 10-minute ride away.

The Great Hammerheads are quite seasonal. You have to be at the site between December and March. One time we went in April and waited nearly three hours to get one shark. The boat the day before us also waited 3 hours, but they got three sharks.

The Oceanic Whitetip dives and the animals’ behaviour are very different.

The oceanics are at Cat Island, down south.

Local fishermen first noticed how many sharks there are at Cat.

For these sharks we fly an hour and then take a boat for another hour before getting to the dive site.

The water there is very deep and we only see the bottom if the current drags us closer to shore.

You drift with the current on those dives. One time we drifted for miles, around two very distant points, and ended up two or three bays away from where we got in.

For these dives the bait box dangles from an untethered buoy and the feeder stays with it. Perhaps the bigger risk on the oceanic dives is that you can forget to watch and limit your depth. The feeders suggest you go no deeper than 15 meters; but one tends to follow some of the sharks when they descend deeper -- or to sink a bit. Sometimes your buoyancy isn’t perfect or you’re not attentive enough to stay shallow.

The more acute and animated feeders, a bit like with the tigers, are very physically active and precise – they move in an acrobatic manner to feed in different directions and in unison with the sharks. Keeping their eyes on multiple sharks, including some that approach from behind, and feeding them at the same time can’t be easy. The best feeder we had managed to watch/be vigilant and feed 4 or 5 oceanic whitetips in close proximity at a time. He just moved and thought and fed right. It was a bit like an underwater, thrilling but dangerous ballet.

The oceanics are often friskier than the tigers and hammers. They’re bolder and more interested. Perhaps because they are open ocean predators and they stumble onto food less often than they’d like. On one dive a shark came and pushed me three times in a row. I pushed it away with my camera each time but was definitely flustered, a bit worried…

On our very first oceanic dive, in 2015, nine sharks showed up. We didn’t even have to chum to bring them in; they arrived within 5 minutes, drawn to the noise of the boat which apparently reminds them of fishing boats they can get scraps from. Keeping our eyes on 9 sharks, a couple of which were much bigger than the others, was challenging. Having only 4 or 5 in our field of vision now and again and knowing there were 4 or 5 out of view, possibly behind us, was a bit daunting.

On other dives at Cat we’ve had anywhere between three and six sharks.

The oceanics are only reliably at Cat Island in April and May.

Without a doubt, oceanic whitetips are my favorite sharks. They are BEAUTIFUL, curious, strong, and their colors are stunning.

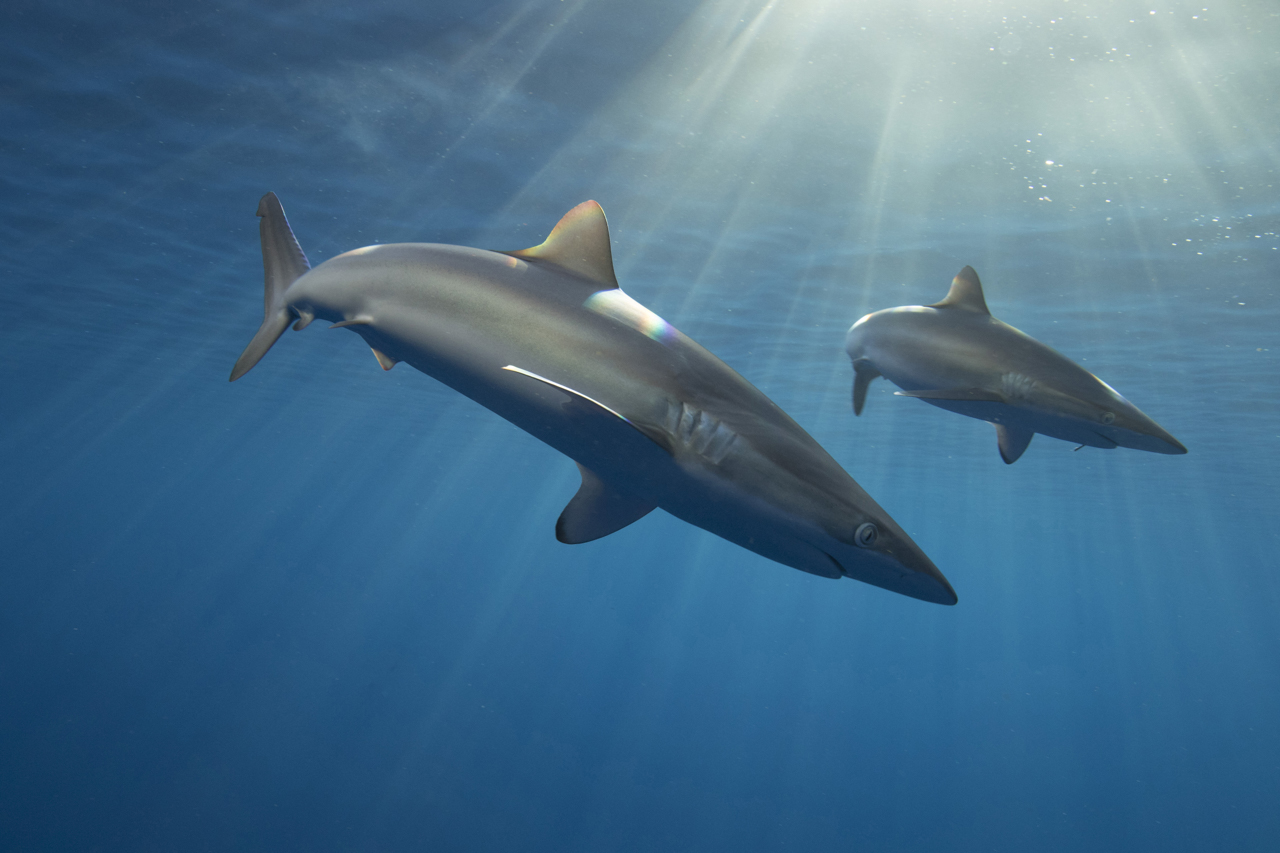

Silky sharks are a close second. They are very sleek, fast and extremely beautiful.

Our feeder used to be a crazy Brazilian guy called Beto. He was 39-years-old and unmarried the year we dove most with the sharks – maybe three years ago. I always used to joke with him and ask if he could please stay alive so that we might employ him to do sharks next season.

He got married the next year and then I joked that now he had something to live for.

He was head diver on all our shark dives and had experience feeding multiple species: great hammerhead, tiger, oceanic and Caribbean reef sharks. He moved from Nassau to St. Lucia a couple of years ago and then to Australia. So now we use different operators/feeders…

I only bring friends who are very skilled divers on these shark dives — particularly with the oceanics, which I think are riskier than the others. I’m much less nervous that a shark might hurt a friend than I am that a friend might panic out of fear, run out of air at the wrong time or swim off clumsily, arms and legs dangling in all directions, if they have a problem.

At this point I have a lot of faith in the sharks — and in most of the feeders. Certainly the experienced ones.

It feels unlikely to me that an accident will happen — unless someone stops paying attention or does something stupid. Having done about six of these oceanic dives now[4], no one has been injured.

But I never want to be complacent, feel overconfident or forget to be vigilant. That’s probably when accidents happen. If you take your safety for granted, think you’re invincible or get lulled into a false sense of security... if you suddenly think all the sharks around you are docile, THAT is a risk. They are top predators, fast and strong, and they are wild animals.

[1] And many tiger and great hammerhead dives

[2] Nictitating membranes -- transparent or translucent third eyelids present in some animals -- can be drawn across the eyelid for protection and to moisten it while maintaining vision.

The eyes of great whites, for example, can easily be scratched by the seals they eat.

[3] That happened to me once – and I could tell immediately because the feeder and my dive buddy suddenly rushed to me to ward the shark off.

[4] Some shark species are seasonal in certain areas. Some, like silky sharks, also migrate…

I’m quite sure that, were it not for films like JAWS, Deep Blue Sea and the Shallows, we wouldn’t be anywhere near as afraid of sharks as we are.

I’m also convinced that the younger you are to experience something considered dangerous, the more likely you are to be ok with it and brave. I was never really afraid of snakes because my siblings and I first handled one with an adult in Sardinia when I was about 9.

With sharks… it seems lucky to me that the first one, a little reef shark, swam by me when I was 14 or 15.

The whole idea that sharks will most likely attack you if they see you in the water is as much of a fallacy as the idea that if you jump into the water with a pod of wild dolphins they will want to play with you.

If one includes species that have only been seen dead or found a small number of times (Megamouth etc.), over 350 different species of shark have been identified. And of those a huge number are sharks you would never see swimming, that live at night, very deep, under ledges or on the ocean floor. Many species of sharks, which are related to rays — also cartilaginous fishes, look nothing like what you imagine a shark looks like. Some are flattened, some guitar-shaped, some look like carpets… Some just look like normal fish with big eyes, strange heads or tails. Shark size ranges from 20 centimeters for the dwarf lantern shark to 18.8 meters for the whale shark – the biggest fish in the sea. The vast majority of shark species have never been known to attack anybody. And humans are decimating sharks at an unprecedented and horrifying rate. We kill 100 to 273 million sharks a year, including those taken for their fins, which are cut off when they’re alive (the sharks are then thrown back into the water, unable to swim and left to die), those entangled in nets and taken by mistake as by-catch. And yet sharks kill only 6 to 8 people a year around the world. So sharks are killing us at perhaps 0.000000029304029 to 0.00000006 the rate we kill them. It is said that overall shark numbers have declined by ninety percent over the past few decades.

It has been an incredible privilege over the years to see perhaps 12 species of sharks, including the zebra, tiger, whale, thresher shark, wobbegong (which looks like a carpet!), the very rare and endangered oceanic white tip, and two species of hammerhead.

Only about 12 times – split between perhaps 4 individual animals – have I felt a shark liked me too much or might, had I been unfortunate, hurt me. Each time I was in the water with dead fish and blood to attract them.

About three times a year, I take friends whose diving skills are unquestionable to see tiger sharks, great hammerheads, and oceanic white tips in the Bahamas.

One pretty much has to draw sharks in with food to see them. Of course you might see a shark at random on a dive, and it might be the species you’re most interested in. But if you want good photographs, including close-ups, and to really get to know a species you need to travel to where it’s commonly seen, go to the site experts and professionals visit, and, usually, throw fish and blood in the water to bring the sharks in.

This chumming is such a common practice in some places, and works so well, that the feeders and guests see the animals nearly every time[1]. In fact, some sharks attend these free meals so often that the feeders can easily identify/recognize them. Emma, for instance, is one of the more famous sharks at Tiger Beach in Grand Bahama.

For tiger sharks we have to travel about an hour and a half to Tiger Beach, in Grand Bahama, which isn’t a beach at all. It’s a sandy bottom - with the odd bit of coral reef here and there - in the same area where we find the spotted dolphins I go and see with the Wild Dolphin Project every summer. Someone told me that it was people searching the area for dolphins who first noticed there are lots of tiger sharks there.

At Tiger Beach the first thing you see when you anchor is a large number of lemon sharks, eager to eat the chum from the shark boats, waiting at the surface. They form a sort of moving, ever-changing circle of diners and eat nearly everything we throw in – while we are actually chumming for tigers. There are more lemon sharks at the bottom, and frequently Caribbean Reef Sharks, too. The Tiger Sharks nearly always come at some point. They’re much bigger, and more colorful, than the other sharks — with their beautiful markings and squarish faces. The least tiger sharks I’ve ever seen on a dive there is 1, the highest number 5. We once waited more than an hour at the surface, chumming over the side of the boat for what seemed like forever, for a tiger to come only at the end of the dive… two hours after we started feeding. Other times a nearby boat already had a tiger when we arrived ... or the shark(s) came very soon after we anchored.

The feeders sometimes stroke the noses of the tiger sharks, and the eyes roll white – to protect from possible damage[2], or push their heads down towards the sand to avoid teeth. Sometimes they keep one hand on the nose and redirect the shark with the other hand on the body, pushing the animal forward or sideways. We’re given plastic sticks, white and about a meter long, to ward sharks off if they come too close, and we’re told never to take our eyes off a tiger shark when it comes near –– to keep looking at them even once they’ve swum past us in case they choose to turn around and approach us from behind.[3] Overall, though, and over the course of 8 or more dives at Tiger Beach, friends and I have rarely been scared of a tiger shark: we haven’t had cause to be.

The original feeder we used, who must have done thousands of shark dives, would joke that he had “two chances” with tiger sharks: they bump something first before they bite it.

Cameras are very good buffers, particularly when strobes are attached, making the rig bigger, and can be used to push sharks away.

The tiger sharks, while impressive — and some of them very big (Emma is 14 feet long!), seem to move slowly... nearly as if it’s a task to carry their heavy bodies around. And one could almost argue that some of the ones at Tiger Beach are unnaturally habituated to people.

There are literally thousands of photos of Tiger Beach, and the tiger (and, occasionally, great hammerhead) sharks there, on Instagram and the Internet. Emma the tiger shark in particular.

For the Great Hammerheads we go to Bimini, which is also prime territory for the Atlantic Spotted Dolphins.

And just like with the tiger sharks, it’s very shallow water, the feeder stands on the sand next to the bait box, and the divers sit in a line or semicircle some distance away, opposite the feeder.

The nicer feeders frequently take fish out of the covered bait box (a crate) and give them to the sharks. The slightly less nice or novice feeders keep the bait box closed nearly all the time, which keeps the sharks around since they still smell the fish and blood in the water; but keeps them unjustly hungry, too!

Where there are lots of lemon sharks and some reef sharks on the tiger dives, there are lots of lazy nurse sharks on the sand, hoping for food and often close to the bait box, on the hammerhead dives. On the hammerhead dives we also frequently see bull sharks, which are considered more dangerous, and are quite girthy.

Great hammerheads are HUGE — reaching up to 6 meters in length , and their dorsal fins are very tall.

They are in the books as some of the more dangerous sharks; but I have never seen one look threatening or come up close on a dive. The last feeders we had said the same thing: they’re not in the least interested in us and, if anything, they avoid us. They come in for the food, barely look at the feeder (“shark wrangler”) or divers, turn away immediately, and then come back for more.

Sometimes they dip their bodies to one side, looking almost diagonal when you see them swim.

The nurse sharks are basically puppies. They sit on the ground, they mill around, they look and are harmless. They just want their food.

Despite their enormous size, and awkward shape, the hammerheads can turn on a dime. You should see the speed with which they swivel over the bait box after taking a fish and before heading away again. One of the theories about the hammer used to be that moving their heads side to side helped them swim faster. Called the cephalofoil, the hammer is apparently occasionally used to hit stingrays and skates, favorite foods, from above. It also serves as a hydrofoil that allows the sharks to turn quickly. Apparently the cephalofoil is also used to detect prey and can pick up the electrical signatures of buried stingrays.

One nice thing about the hammer dives is that once we’ve arrived at the airport and got on the boat, the shark-feeding spot is only a 10-minute ride away.

The Great Hammerheads are quite seasonal. You have to be at the site between December and March. One time we went in April and waited nearly three hours to get one shark. The boat the day before us also waited 3 hours, but they got three sharks.

The Oceanic Whitetip dives and the animals’ behaviour are very different.

The oceanics are at Cat Island, down south.

Local fishermen first noticed how many sharks there are at Cat.

For these sharks we fly an hour and then take a boat for another hour before getting to the dive site.

The water there is very deep and we only see the bottom if the current drags us closer to shore.

You drift with the current on those dives. One time we drifted for miles, around two very distant points, and ended up two or three bays away from where we got in.

For these dives the bait box dangles from an untethered buoy and the feeder stays with it. Perhaps the bigger risk on the oceanic dives is that you can forget to watch and limit your depth. The feeders suggest you go no deeper than 15 meters; but one tends to follow some of the sharks when they descend deeper -- or to sink a bit. Sometimes your buoyancy isn’t perfect or you’re not attentive enough to stay shallow.

The more acute and animated feeders, a bit like with the tigers, are very physically active and precise – they move in an acrobatic manner to feed in different directions and in unison with the sharks. Keeping their eyes on multiple sharks, including some that approach from behind, and feeding them at the same time can’t be easy. The best feeder we had managed to watch/be vigilant and feed 4 or 5 oceanic whitetips in close proximity at a time. He just moved and thought and fed right. It was a bit like an underwater, thrilling but dangerous ballet.

The oceanics are often friskier than the tigers and hammers. They’re bolder and more interested. Perhaps because they are open ocean predators and they stumble onto food less often than they’d like. On one dive a shark came and pushed me three times in a row. I pushed it away with my camera each time but was definitely flustered, a bit worried…

On our very first oceanic dive, in 2015, nine sharks showed up. We didn’t even have to chum to bring them in; they arrived within 5 minutes, drawn to the noise of the boat which apparently reminds them of fishing boats they can get scraps from. Keeping our eyes on 9 sharks, a couple of which were much bigger than the others, was challenging. Having only 4 or 5 in our field of vision now and again and knowing there were 4 or 5 out of view, possibly behind us, was a bit daunting.

On other dives at Cat we’ve had anywhere between three and six sharks.

The oceanics are only reliably at Cat Island in April and May.

Without a doubt, oceanic whitetips are my favorite sharks. They are BEAUTIFUL, curious, strong, and their colors are stunning.

Silky sharks are a close second. They are very sleek, fast and extremely beautiful.

Our feeder used to be a crazy Brazilian guy called Beto. He was 39-years-old and unmarried the year we dove most with the sharks – maybe three years ago. I always used to joke with him and ask if he could please stay alive so that we might employ him to do sharks next season.

He got married the next year and then I joked that now he had something to live for.

He was head diver on all our shark dives and had experience feeding multiple species: great hammerhead, tiger, oceanic and Caribbean reef sharks. He moved from Nassau to St. Lucia a couple of years ago and then to Australia. So now we use different operators/feeders…

I only bring friends who are very skilled divers on these shark dives — particularly with the oceanics, which I think are riskier than the others. I’m much less nervous that a shark might hurt a friend than I am that a friend might panic out of fear, run out of air at the wrong time or swim off clumsily, arms and legs dangling in all directions, if they have a problem.

At this point I have a lot of faith in the sharks — and in most of the feeders. Certainly the experienced ones.

It feels unlikely to me that an accident will happen — unless someone stops paying attention or does something stupid. Having done about six of these oceanic dives now[4], no one has been injured.

But I never want to be complacent, feel overconfident or forget to be vigilant. That’s probably when accidents happen. If you take your safety for granted, think you’re invincible or get lulled into a false sense of security... if you suddenly think all the sharks around you are docile, THAT is a risk. They are top predators, fast and strong, and they are wild animals.

[1] And many tiger and great hammerhead dives

[2] Nictitating membranes -- transparent or translucent third eyelids present in some animals -- can be drawn across the eyelid for protection and to moisten it while maintaining vision.

The eyes of great whites, for example, can easily be scratched by the seals they eat.

[3] That happened to me once – and I could tell immediately because the feeder and my dive buddy suddenly rushed to me to ward the shark off.

[4] Some shark species are seasonal in certain areas. Some, like silky sharks, also migrate…

A Scalloped Hammerhead rises up the slope

At the famed Manuelita site, Cocos, June 2017

We all had to hold our breaths for much of the Manuelita dives – so as not to scare the shy Hammerheads away with our bubbles.

It was hard both to get them close and to take good pictures.

Cocos island is, according to Sylvia Earle, “one of the sharkiest places on Earth”!

It is STUNNING there. I was privileged to join an expedition with Sylvia and her Mission Blue

Team a couple of years ago.

Cocos is pretty much a protected Costa Rican island full of rainforests, with waterfalls pouring down

Rock faces into the ocean, its waters a very rich ecosystem with schools of large and pelagic fish like tuna swimming through and hundreds and hundreds (thousands during the right season) of Scalloped

Hammerheads.

Galapagos sharks and whitetip reef sharks, which hunt at night and will actively do so under the torches of divers, also abound.

Since the water started getting warmer a few years ago, tiger sharks have started showing up as well.

Plenty of other dive sites exist (Punta Maria, where the image of the scarred Galapagos shark was taken, and Halcyon, which is very deep and where the currents can be treacherous, come to mind) but by far the best site for hammerheads is a fairly shallow reef (20 meters), with rows of rocky ledges you can sit or crouch on, called Manuelita.

The hammerheads get cleaned there by barber fish, and they swim around and climb up and down the reef vertically as well.

Hammerheads are notoriously skittish and stay far away from divers. So in order to get good photos – not to deter the sharks from coming close – people need to hold their breath.

All of us on these dives at Manuelita were doing our very best not to breathe out at the wrong time, causing an eruption of bubbles that would scare the sharks away.

The above image is the best I have of a scalloped hammerhead. One thing I love about it is that the shark looks nearly silver in color even though the shark was actually grey.

This version of the photograph was touched up – “color corrected “ – by the top retouching person at National Geographic, Mike Lappin.

At the famed Manuelita site, Cocos, June 2017

We all had to hold our breaths for much of the Manuelita dives – so as not to scare the shy Hammerheads away with our bubbles.

It was hard both to get them close and to take good pictures.

Cocos island is, according to Sylvia Earle, “one of the sharkiest places on Earth”!

It is STUNNING there. I was privileged to join an expedition with Sylvia and her Mission Blue

Team a couple of years ago.

Cocos is pretty much a protected Costa Rican island full of rainforests, with waterfalls pouring down

Rock faces into the ocean, its waters a very rich ecosystem with schools of large and pelagic fish like tuna swimming through and hundreds and hundreds (thousands during the right season) of Scalloped

Hammerheads.

Galapagos sharks and whitetip reef sharks, which hunt at night and will actively do so under the torches of divers, also abound.

Since the water started getting warmer a few years ago, tiger sharks have started showing up as well.

Plenty of other dive sites exist (Punta Maria, where the image of the scarred Galapagos shark was taken, and Halcyon, which is very deep and where the currents can be treacherous, come to mind) but by far the best site for hammerheads is a fairly shallow reef (20 meters), with rows of rocky ledges you can sit or crouch on, called Manuelita.

The hammerheads get cleaned there by barber fish, and they swim around and climb up and down the reef vertically as well.

Hammerheads are notoriously skittish and stay far away from divers. So in order to get good photos – not to deter the sharks from coming close – people need to hold their breath.

All of us on these dives at Manuelita were doing our very best not to breathe out at the wrong time, causing an eruption of bubbles that would scare the sharks away.

The above image is the best I have of a scalloped hammerhead. One thing I love about it is that the shark looks nearly silver in color even though the shark was actually grey.

This version of the photograph was touched up – “color corrected “ – by the top retouching person at National Geographic, Mike Lappin.

Side view of a Great Hammerhead’s face, teeth and all…

A Remora on top and a small one under the Hammer…

Bimini, The Bahamas, December 2014

Much as this is a good picture my eye is inevitably and invariably drawn to the blotches.

That site has very fine sand, which you and other divers tend to kick up, and which the sharks also move when they come to eat.

In this image one can see grains of sand floating around.

One reason this photograph is interesting perhaps is that hammerhead teeth are rarely seen from this angle… and this specific hammerhead was badly in need of an orthodontist!

There’s one thing I find fascinating about hammerheads – and also manta rays – which is that it can be hard to distinguish where the eye starts and how it’s separate from the body. Their eyes sometimes look completely blended with the rest of them.

A Remora on top and a small one under the Hammer…

Bimini, The Bahamas, December 2014

Much as this is a good picture my eye is inevitably and invariably drawn to the blotches.

That site has very fine sand, which you and other divers tend to kick up, and which the sharks also move when they come to eat.

In this image one can see grains of sand floating around.

One reason this photograph is interesting perhaps is that hammerhead teeth are rarely seen from this angle… and this specific hammerhead was badly in need of an orthodontist!

There’s one thing I find fascinating about hammerheads – and also manta rays – which is that it can be hard to distinguish where the eye starts and how it’s separate from the body. Their eyes sometimes look completely blended with the rest of them.

Bar jacks ahead of -- and a remora below -- "Lady hook" the Tiger Shark

Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, July 2014

Like most of the tiger sharks that come in for feeding at Tiger Beach, Lady Hook is female.

She was my first ever tiger shark and she had a large hook in her mouth.

The fish in front of her are not pilot fish, which are black and white; they are juvenile jacks.

Tiger Beach is not a beach at all. It’s a large area of shallow water with a sandy bottom frequented by high numbers of tiger sharks.

Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, July 2014

Like most of the tiger sharks that come in for feeding at Tiger Beach, Lady Hook is female.

She was my first ever tiger shark and she had a large hook in her mouth.

The fish in front of her are not pilot fish, which are black and white; they are juvenile jacks.

Tiger Beach is not a beach at all. It’s a large area of shallow water with a sandy bottom frequented by high numbers of tiger sharks.

Close-up of a Lemon Shark at Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, April 2014

Lemon sharks are much more common than tiger sharks at Tiger Beach. The ratio has been something like 12 to 1 on my every dive there.

The lemons are greedier than the tigers and, although their teeth seem formidable, they are totally inoffensive.

Their faces are often quite funny. They tend to be covered with remoras at this dive site.

Lemon sharks are much more common than tiger sharks at Tiger Beach. The ratio has been something like 12 to 1 on my every dive there.

The lemons are greedier than the tigers and, although their teeth seem formidable, they are totally inoffensive.

Their faces are often quite funny. They tend to be covered with remoras at this dive site.

Oceanic Whitetip shadowed by pilot fish

Cat Island, The Bahamas, April 2015

From my first ever dive with Oceanics. 9 sharks showed up before we even started chumming the water.

They were drawn to the noise of the boat engine.

Cat Island, The Bahamas, April 2015

From my first ever dive with Oceanics. 9 sharks showed up before we even started chumming the water.

They were drawn to the noise of the boat engine.

It’s hard to believe that this is actually one of the 400 plus species of shark!

This one is a Tasselled Wobbegong – a member of the very aptly named group of “carpet sharks”.

Raja Ampat, Indonesia, August 2015

Tasselled Wobbegongs inhabit coral reefs and can reach a length of 1.8 meters.

This one is a Tasselled Wobbegong – a member of the very aptly named group of “carpet sharks”.

Raja Ampat, Indonesia, August 2015

Tasselled Wobbegongs inhabit coral reefs and can reach a length of 1.8 meters.

A Great White Shark off the North Neptune Islands, Australia, in 2015

My camera disobeyed me the whole trip and I only have about 3 decent shots from maybe 12 cage dives.

My camera disobeyed me the whole trip and I only have about 3 decent shots from maybe 12 cage dives.

My favourite portrait of a Tiger Shark!

Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, April 2016

I love the scar on the nose.

This shark was very curious and, although it wasn’t acting aggressively, the “safety diver” next to me warded it off with one of the large plastic sticks we dive with at the site.

Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, April 2016

I love the scar on the nose.

This shark was very curious and, although it wasn’t acting aggressively, the “safety diver” next to me warded it off with one of the large plastic sticks we dive with at the site.

Pregnant Tiger Shark!

Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, April 2016

This is probably “Emma”, the famous 14-foot tiger shark who regularly comes to be fed there and can be seen in Instagram post after Instagram post, video after video.

She’s quite docile and has never hurt anyone. Docile but huge…

Tiger Beach, Grand Bahama, April 2016

This is probably “Emma”, the famous 14-foot tiger shark who regularly comes to be fed there and can be seen in Instagram post after Instagram post, video after video.

She’s quite docile and has never hurt anyone. Docile but huge…

A Silky Shark, hooked

The Exumas, April 2016

Unfortunately about a third of the sharks I see in the Bahamas have a hook in their mouths – or a scar from a past fishing accident.

The Exumas, April 2016

Unfortunately about a third of the sharks I see in the Bahamas have a hook in their mouths – or a scar from a past fishing accident.

A beautiful Thresher Shark nearly 30 meters down sometime after 5 a.m. (sunrise) at Malapascua in the Philippines, May 2017

Threshers live deep down and stun their prey with their long tails.

There are 3 different species. The enormous eyes of one species are adapted to see better in the dark.

We weren’t allowed to use flash and the light that deep is terrible – making photography hard.

Malapascua is the only really reliable place in the world to see thresher sharks.

Threshers live deep down and stun their prey with their long tails.

There are 3 different species. The enormous eyes of one species are adapted to see better in the dark.

We weren’t allowed to use flash and the light that deep is terrible – making photography hard.

Malapascua is the only really reliable place in the world to see thresher sharks.

Whitetip Reef Sharks on the seafloor -- quite shallow here.

Isla del Coco, Costa Rica, June 2017

Whitetip Reef Sharks stay fairly small and are generally quite inactive.

You usually see them just lying on the floor, appearing to breathe heavily; but they’re often found in caves as well. They are nocturnal, which probably explains the low energy.

But at Cocos divers can watch them feed frantically on night dives. The sharks gather under the light of the dive torches and hunt fish relentlessly, giving divers a real spectacle.

Isla del Coco, Costa Rica, June 2017

Whitetip Reef Sharks stay fairly small and are generally quite inactive.

You usually see them just lying on the floor, appearing to breathe heavily; but they’re often found in caves as well. They are nocturnal, which probably explains the low energy.

But at Cocos divers can watch them feed frantically on night dives. The sharks gather under the light of the dive torches and hunt fish relentlessly, giving divers a real spectacle.

A large Galapagos Shark with a heavily scarred face cruises

About 30 meters down at the Punta Maria site.

Isla Del Coco, June 2017

I assume this scar is the result of a fishing accident. Illegal fishing is rampant at Cocos, and has hit the hammerheads particularly hard. It’s an absolute tragedy since Cocos is one of the “sharkiest” places on earth and needs to remain well-protected and patrolled.

The first dive we did at Punta Maria we saw nearly no sharks – and scared the ones we saw away by moving too much or swimming too fast. On the second dive we were much stealthier and we saw this Galapagos shark.

About 30 meters down at the Punta Maria site.

Isla Del Coco, June 2017

I assume this scar is the result of a fishing accident. Illegal fishing is rampant at Cocos, and has hit the hammerheads particularly hard. It’s an absolute tragedy since Cocos is one of the “sharkiest” places on earth and needs to remain well-protected and patrolled.

The first dive we did at Punta Maria we saw nearly no sharks – and scared the ones we saw away by moving too much or swimming too fast. On the second dive we were much stealthier and we saw this Galapagos shark.

A large Galapagos Shark accompanied by Blue-spotted Trevallies -- Jacks -- about 25 meters down at the Punta Maria site, Isla del Coco, in June 2017

The range of the Galapagos Shark is not limited to the Galapagos islands.

The range of the Galapagos Shark is not limited to the Galapagos islands.

A Silky Shark less than 5 minutes away from home.

At the site we call “Silky” in the Exumas, December 2017

Silky Sharks are my favourite sharks along with Oceanic Whitetips.

Although silkies can grow to 2.5 meters long, the ones close to home are small. In fact, I’ve never seen one bigger than 1M 30 in the Bahamas.

They are beautiful and sleek – and they look wonderful with flash! The silkies I photograph are very fast – so much so that, if they were bigger, they might scare you.

They often come right up to my camera and even get tangled in my strobe cables sometimes.

At the site we call “Silky” in the Exumas, December 2017

Silky Sharks are my favourite sharks along with Oceanic Whitetips.

Although silkies can grow to 2.5 meters long, the ones close to home are small. In fact, I’ve never seen one bigger than 1M 30 in the Bahamas.

They are beautiful and sleek – and they look wonderful with flash! The silkies I photograph are very fast – so much so that, if they were bigger, they might scare you.

They often come right up to my camera and even get tangled in my strobe cables sometimes.

Silky Sharks at the “Silky” site,

Exumas, December 2017

“Silky” is a deep dive site, but the sharks are nearly always close to the surface.

The light on this specific day was absolutely beautiful and nearly every photograph I took came out well.

Silky sharks are migratory and we never see them in July when the water is warm. But we see them on every dive at this site in April and December.

Silkies are one of the most abundant shark species in the world. That may not last much longer – because the finning industry is putting immense pressure on them.

Exumas, December 2017

“Silky” is a deep dive site, but the sharks are nearly always close to the surface.

The light on this specific day was absolutely beautiful and nearly every photograph I took came out well.

Silky sharks are migratory and we never see them in July when the water is warm. But we see them on every dive at this site in April and December.

Silkies are one of the most abundant shark species in the world. That may not last much longer – because the finning industry is putting immense pressure on them.

Probably the best frame of an Oceanic Whitetip Shark I’ve ever taken.

We had maybe 4 Oceanics that day at Elphinstone in Egypt, December 2017.

Oceanic Whitetips are very photogenic and curious anyway; but this day was exceptional.

One of the sharks went from one group of divers to the next, moved in and out of the groups and came extremely close to the divers. That shark is the one in this image. It came straight at me (but not aggressively) several times.

This whole series of photographs is interesting because the pilot fish accompanying the shark kept changing position, creating different shapes in my images.

We had maybe 4 Oceanics that day at Elphinstone in Egypt, December 2017.

Oceanic Whitetips are very photogenic and curious anyway; but this day was exceptional.

One of the sharks went from one group of divers to the next, moved in and out of the groups and came extremely close to the divers. That shark is the one in this image. It came straight at me (but not aggressively) several times.

This whole series of photographs is interesting because the pilot fish accompanying the shark kept changing position, creating different shapes in my images.

Oceanic Whitetip Shark accompanied by Pilotfish at Elphinstone Reef,

Egypt, November 2017

Oceanics are open ocean predators and very bold.

You always see them with pilot fish…

Egypt, November 2017

Oceanics are open ocean predators and very bold.

You always see them with pilot fish…

Motion blur photograph of the famous, and famously docile, Nurse Sharks at Compass Cay in the Bahamas, June 2018

There are 12 or more Nurse Sharks the locals have named that live – and live to be fed – at Compass!

People get in and swim among them nearly all hours of the day, including during feedings.

There are 12 or more Nurse Sharks the locals have named that live – and live to be fed – at Compass!

People get in and swim among them nearly all hours of the day, including during feedings.

A Silky Shark surrounded by large Rainbow Runners at the famous buoy in Andros.

The Bahamas, April 2019.

When my buddy and I dove the buoy at Andros there were about 9 sharks swimming about.

One of them was much bigger than the others (though still less than 2 meters long).

Two of them had rainbow runners for company – and they were by far the most interesting to photograph. I don’t know exactly how the rainbow runners might benefit from the sharks or vice versa.

The Bahamas, April 2019.

When my buddy and I dove the buoy at Andros there were about 9 sharks swimming about.

One of them was much bigger than the others (though still less than 2 meters long).

Two of them had rainbow runners for company – and they were by far the most interesting to photograph. I don’t know exactly how the rainbow runners might benefit from the sharks or vice versa.