Tofua’a! (“Whale” in Tongan)

Neiafu, Vava’u, is a reverie. On a less than 1-kilometer strip you have 3 Chinese-run supermarkets; the laundromat called Bubbles (!!) run by a Vanessa and a Glenn; the stunning blue and white church with its melodic singing and full Sunday crowd (Tongans are very religious, and no one works on Sundays1); two banks with much-needed ATMs that provide local money; Bellavista — the delicious Italian place owned by Mario from Orvieto who’s married to Milo, the Tongan lady who manages it2; the waterfront Mango Café, which has more of a comfort food menu; a quiet and picturesque main street and pavements with the pitter patter of dozens of stray, some beautiful and some gruff, dogs... Tropical Tease, the fantastic T shirt shop with dozens of local choices for front and back, connected to the coffee shop and run by a Cindy and an Isa N’ Tim; and the apartments I rent every year called “the boat houses”. The boathouses are just across the bendy street from the fairly new Basque Tavern, which serves tapas, and have one of the most phenomenal, soul-soothing views I’ve ever seen — looking directly at the bay, the docks below us, islands in front and sunset we call home for 2 weeks a year.

Much of the activity in Neiafu revolves around the boats from companies that, combined, have 22 licenses that allow people to go and swim with the humpbacks. Companies with names like Dolphin Pacific, Whales in The Wild, and Beluga.

For some reason everybody in Neiafu always seems happy, everybody mingles, you never witness discord, and people learn each other’s names very fast. Everyone is interconnected, entwined, enchanted.

If you are a repeat visitor in this lovely small town (as I am), drunk on the excitement of whale swims and sightings, surrounded by whale-related shop offerings and familiar faces, it literally feels like you have a small, if extended, family and home away from home.

The more I visit Vava’u the more I realize I might never stop coming here and will want to take friends every season — with numbers limited only due to the restriction of 5 people in the water, guide included, at a time with the whales.

The encounters we have with whales in Tonga can generally be divided into 3 categories: heat run, mother and calf (and sometimes escort); adult whale(s).

Heat runs are all chaos, speed, and lust. On a heat run you have multiple males seeking and competing for the affection of one female. Occasionally the female will be a mother who has her calf with her — and you feel bad that this child has to watch its mum be chased by multiple lustful and highly determined males. Also because calves are much less used to swimming at high speed (heat runs are fast) and they must get absolutely exhausted.

I have personally never seen more than 10 whales in a heat run (and I only saw ten once), but you’ll hear from other people in Vava’u, who frequently exaggerate — tourist and local alike, that they have seen heat runs with up to 22 or more whales. I have seen photographs with 14 or 15 whales.

I asked our intrepid and highly experienced guide, an ex-firefighter from Birmingham called Alistair, how the female picks a mate among her many suitors. Does she pick for instance by looks, intelligence, sense of humor, socio-economic status? Something else? Al answered that she nearly always ends up with the most persistent male. Many whales “drop off” after some time (some are even quite lazy!). Even the diehard pursuers abandon the chase after a while, and whoever sticks around apparently gets lucky.

Heat runs are usually frustratingly fast, chaotic and therefore very hard to photograph. The group of whales shoots past you ridiculously fast even if you’re dropped a hundred meters in front of them. They’re often pointing in different directions, never in single file, and you barely have time to aim with the camera, let alone focus on the animals, by the time they pass by.

Much as they are “exciting” and fascinating I always find heat runs harder and more frustrating than enjoyable or pleasant.

“Mums and calves” are, at least to the casual observer, where all the love, emotion, devotion, protection, nurturing, kindness, mutual interest, and mirrored positions are.

The sense of care, love and concern, pride and protection you get from a mother is indescribable and unfathomable.

They are watching their calves and assessing you every single second you spend in the water with them.

Some mothers are much more nervous, protective and defensive than others. They will pull their calves away from your group long before everyone settles or very early -- as soon as they consider the calf has come too close to you or you to it. Other mothers just hang under the surface, clearly still watching intently but much less concerned, and let their child do its thing uninterrupted, without interference.

Adult humpbacks in Vava’u only stay down for maybe 25 minutes — even though they can hold their breaths longer3 — whereas the calves have to come up every 3 to 5 minutes. So if you’re lucky enough to have a 10- or more-minute swim you’ll probably see the calf rise for a breath 3 or more times.

Some calves, whether by nature or in response to their mother’s behavior, just rise and descend away from swimmers and directly above their mother. Others are thrillingly curious, confident and trusting. They won’t hesitate to swim close to your group, even meander between people... and if you are truly very lucky indeed, they might bump you on their little tour! Despite significant size at such a young age, they are rarely clumsy, they mean you no harm, and their skin just feels like hard rubber. The water also absorbs much of the shock. I’ve only ever heard one person complain about pain when bumped by a calf.

To me it has always felt like an immense honor and a rush of joy between the start of a calf’s approach and when it ends up meters away after the bump.

Adult whales are much bigger, heavier and stronger, and they often have barnacles on their pectoral fins, tails or both. So you want to avoid getting hit by a fin or (larger and stronger) tail as much as possible. We’re told to stay 10 meters away from the whales at all times anyway, and particularly mothers and calves so as not to fluster them; but frequently the whales will approach you or the current move you.

Calves often mirror the position of their mothers and seem (are) incredibly bound to them. I have one series of photographs from 2015 in which the mother and calf have the exact same position of their pectoral fins over 30 photographs during a 10-minute swim, and it’s incredible to look back.

The sweetest moments are when a calf will settle under its mother’s nose or fin when it’s descended after a breath. Or when a calf rests on its mother’s nose at the surface.

Another fantastic image you will never forget is when mother and calf are side-to-side, touching one another and looking ahead together in unison.

It is very clear when a mother wants an encounter to end. She will whisk her calf away with total determination and sometimes at impressive speed.

Frequently it is the escort, a suitor but not the father, who decides when it’s time to go. He will put himself directly between you and the others or simply move them off.

Sometimes a mother has 2 escorts; but usually – if she has one at all – it’s one. Escorts frequently stay a little in the background or slightly deeper than the mother and calf.

It’s in an escort’s interest to stay close, be protective and to limit competition from other males for the female’s affection.

An escort is frequently more wary of swimmers and keener to interfere than the mother is.

The other typical situation we get is adult whale(s).

Whether one whale or multiple, one sex or both, it’s very distinct from mother and calf and also distinct from a heat run (even if there is such a thing as a mini heat run, which consists of a smaller group of whales).

Sometimes we stumble on a lone individual, sometimes a pair or trio. Their behaviour and the extent to which they interact, whether with you or each other, varies tremendously.

At times, the best you can hope for is to hover over a whale in the water as it rests and watch it rise to the surface when it’s ready to breathe. If you’re unlucky you will experience nothing but this time after time with one whale or group. The whale in question might never turn towards you, interact with another whale, or even come close enough for you to get a good look.

But when they’re good, adult whales can also be amazing.

Photographing - and even seeing - the whales is a real challenge when they’re deep.

In deep, dark water (the waters around Vava’u are generally very deep) it’s hard to identify dark bodies. Much of the time, the only way to notice the whales deep is when the white patches on their sides or their bellies are showing.

Two of my favorite moments are before and while the whales rise. At first, if you haven’t been looking at the white patches on their sides or seen their bellies, you see the tip of the nose and nodules on it. Sometimes the nose is paler, which helps to see, and sometimes not.

But as they rise the nose becomes bigger and bigger in your sight. You realize how big and graceful the whales are with every second they come closer to you, every meter closer to the surface. And you can’t understand for the life of you why those nodules are there or what function they serve.

The other thing I love about watching the whales when they’re under is the decision point - or multiple decision points - before they rise.

Their pectoral fins are perpendicular from their sides when immobile or resting; but they have to bring the fins towards each other before they rise. There is always a first flutter of the fins, like the beginning of a decision, before multiple consecutive flutters or just a slow concerted pull into the rising position.

As they rise the whales decide where to turn – towards you or away from you. And if you’re lucky they will come directly towards you, head to head, or rotate on their axis to show you their white undersides before they turn away.

Sometimes they hang… Most of the whales spend all their time below the surface horizontal, only going vertical to rise. Others stay vertical, as if just waiting at the ready, much of the time below the surface. One mother a few seasons ago had her head pointing to the bottom and tail to the sky!

Sometimes they roll… Roll over, whether horizontal or vertical, and show you their beautiful, white stomachs and throats — ridges of skin and all.

For friendly and interested calves, rolling seems quite frequent — like they’ve learned a new trick, are practicing and showing off at the same time.

Sometimes an adult will roll as well… or even roll repeatedly as you swim next to it. In the case of an adult rolling it really feels like an intentional and highly conscious thing, as if they’re doing it for you... whereas calves might be doing it for their own amusement as much as yours.

Sometimes whales CHASE you or rush you!

“Crazy George” was practically pushing me, his eye a meter from mine and nose against my flipper, on a swim in August last year. I tried to swim away from him as fast as I could three times, but each time he was still right on me. Crazy George has been known to lift people out of the water on his head!

Another whale, our first of the season two years ago, saw my guide Alistair Coldrick and me and that very second rushed us as fast as he could. He/she rushed us at high speed from about twenty meters away until he/she dove about 5 meters in front of us!

And then again this year: we had TWO whales acting crazy on an encounter with us. One of them kept turning towards us as we swam parallel to it — constantly forcing us to turn and getting too close for comfort (no one wants to hurt an animal. Nor be hurt by one) — And nearly lifted my friend on its pectoral fin. The other whale stayed far off for most of the time but would then suddenly come into the mix, unexpected, from out of the blue, jarring us with its speed and unpredictability.

Sometimes they breach… One usually only sees breaching from fairly far away – as one does tail slapping and fin slapping at the surface. It’s rare to have a whale breach close to you while you’re in the water. But it can happen. Unfortunately it’s also rare that the whales stick around and interact with you after they’ve been playing at the surface, slapping or breaching, for minutes. Even when it looks like they’re inviting you to come in and join them, they often let you down by swimming off!

Sometimes they float up… This summer, we saw a calf so young and inexperienced that it was still working on its buoyancy. Instead of gently tilting toward the surface headfirst, it floated up bottom first with nearly no control!

Sometimes you don’t even notice how a horizontal whale below the surface suddenly got 6 meters closer to you without having visibly moved. As if the animal can rise without making a single effort.

The visibility in the water can be remarkably bad – this has been the case during 2 of the 5 seasons I’ve visited – and a large number of images of the Vava’u whales you see on the Internet, including by lauded and well-known photographers, are massively touched up.

As often as possible I keep my images nearly entirely true to the situation they were taken in. But in most cases you don’t want dozens of green strands in your whale picture.

We swim hard in Tonga! Looking at beautiful images during the off season allows you to forget how hard you swim for them. You sometimes remember immobile mothers and calves that took no energy and forget a heat run that took seven swims out of you.

But each experience is worth every kick.

Swimming with whales is unbelievably rewarding. As corny as it sounds… the whales do “change your life”. They’re simply too majestic, too enormous, too touching and too intelligent not to.

Just as with humans there’s virtually no way to assess or predict an animal’s character, mood or behaviour ahead of time.

Some days “Crazy George” might just want to swim around in peace. Some days a reserved whale or introspective dolphin might experiment with you, might be in a fun mood and decide to play.

Likewise there is no understanding why one mother whale will be so nervous and worried and swim away at light speed at the sight of a swimmer, whisking her calf away, where another mother chooses to just stay put, unflinching and relaxed, while multiple people observe with joy as her calf swims about unbridled and unconstrained.

Everything depends entirely on the individual.

It might take 6 different whales that are mediocre or flee before you find one great one that doesn’t.

Sometimes you try the same animals that are completely disinterested several times before their mood changes and they suddenly give you magic.

With the dolphins in the Bahamas it’s the same principle. Sometimes there are 20 dolphins in the water and they disappear when you jump in.

Sometimes only 2 dolphins and they stay with you for 3 hours. Sometimes you’re with one group of animals and another one comes from nowhere and joins in.

And on some days you don’t see a single animal at all.

1. Nine out of ten restaurants are closed. Not a single work boat, whale or other guide goes out on Sunday

2. Bellavista’s lovely staff includes waitresses Jay, Eta, Seini and Taina.

3. I was told recently that a whale in Moorea stayed down for 40 minutes at one point this summer.

Neiafu, Vava’u, is a reverie. On a less than 1-kilometer strip you have 3 Chinese-run supermarkets; the laundromat called Bubbles (!!) run by a Vanessa and a Glenn; the stunning blue and white church with its melodic singing and full Sunday crowd (Tongans are very religious, and no one works on Sundays1); two banks with much-needed ATMs that provide local money; Bellavista — the delicious Italian place owned by Mario from Orvieto who’s married to Milo, the Tongan lady who manages it2; the waterfront Mango Café, which has more of a comfort food menu; a quiet and picturesque main street and pavements with the pitter patter of dozens of stray, some beautiful and some gruff, dogs... Tropical Tease, the fantastic T shirt shop with dozens of local choices for front and back, connected to the coffee shop and run by a Cindy and an Isa N’ Tim; and the apartments I rent every year called “the boat houses”. The boathouses are just across the bendy street from the fairly new Basque Tavern, which serves tapas, and have one of the most phenomenal, soul-soothing views I’ve ever seen — looking directly at the bay, the docks below us, islands in front and sunset we call home for 2 weeks a year.

Much of the activity in Neiafu revolves around the boats from companies that, combined, have 22 licenses that allow people to go and swim with the humpbacks. Companies with names like Dolphin Pacific, Whales in The Wild, and Beluga.

For some reason everybody in Neiafu always seems happy, everybody mingles, you never witness discord, and people learn each other’s names very fast. Everyone is interconnected, entwined, enchanted.

If you are a repeat visitor in this lovely small town (as I am), drunk on the excitement of whale swims and sightings, surrounded by whale-related shop offerings and familiar faces, it literally feels like you have a small, if extended, family and home away from home.

The more I visit Vava’u the more I realize I might never stop coming here and will want to take friends every season — with numbers limited only due to the restriction of 5 people in the water, guide included, at a time with the whales.

The encounters we have with whales in Tonga can generally be divided into 3 categories: heat run, mother and calf (and sometimes escort); adult whale(s).

Heat runs are all chaos, speed, and lust. On a heat run you have multiple males seeking and competing for the affection of one female. Occasionally the female will be a mother who has her calf with her — and you feel bad that this child has to watch its mum be chased by multiple lustful and highly determined males. Also because calves are much less used to swimming at high speed (heat runs are fast) and they must get absolutely exhausted.

I have personally never seen more than 10 whales in a heat run (and I only saw ten once), but you’ll hear from other people in Vava’u, who frequently exaggerate — tourist and local alike, that they have seen heat runs with up to 22 or more whales. I have seen photographs with 14 or 15 whales.

I asked our intrepid and highly experienced guide, an ex-firefighter from Birmingham called Alistair, how the female picks a mate among her many suitors. Does she pick for instance by looks, intelligence, sense of humor, socio-economic status? Something else? Al answered that she nearly always ends up with the most persistent male. Many whales “drop off” after some time (some are even quite lazy!). Even the diehard pursuers abandon the chase after a while, and whoever sticks around apparently gets lucky.

Heat runs are usually frustratingly fast, chaotic and therefore very hard to photograph. The group of whales shoots past you ridiculously fast even if you’re dropped a hundred meters in front of them. They’re often pointing in different directions, never in single file, and you barely have time to aim with the camera, let alone focus on the animals, by the time they pass by.

Much as they are “exciting” and fascinating I always find heat runs harder and more frustrating than enjoyable or pleasant.

“Mums and calves” are, at least to the casual observer, where all the love, emotion, devotion, protection, nurturing, kindness, mutual interest, and mirrored positions are.

The sense of care, love and concern, pride and protection you get from a mother is indescribable and unfathomable.

They are watching their calves and assessing you every single second you spend in the water with them.

Some mothers are much more nervous, protective and defensive than others. They will pull their calves away from your group long before everyone settles or very early -- as soon as they consider the calf has come too close to you or you to it. Other mothers just hang under the surface, clearly still watching intently but much less concerned, and let their child do its thing uninterrupted, without interference.

Adult humpbacks in Vava’u only stay down for maybe 25 minutes — even though they can hold their breaths longer3 — whereas the calves have to come up every 3 to 5 minutes. So if you’re lucky enough to have a 10- or more-minute swim you’ll probably see the calf rise for a breath 3 or more times.

Some calves, whether by nature or in response to their mother’s behavior, just rise and descend away from swimmers and directly above their mother. Others are thrillingly curious, confident and trusting. They won’t hesitate to swim close to your group, even meander between people... and if you are truly very lucky indeed, they might bump you on their little tour! Despite significant size at such a young age, they are rarely clumsy, they mean you no harm, and their skin just feels like hard rubber. The water also absorbs much of the shock. I’ve only ever heard one person complain about pain when bumped by a calf.

To me it has always felt like an immense honor and a rush of joy between the start of a calf’s approach and when it ends up meters away after the bump.

Adult whales are much bigger, heavier and stronger, and they often have barnacles on their pectoral fins, tails or both. So you want to avoid getting hit by a fin or (larger and stronger) tail as much as possible. We’re told to stay 10 meters away from the whales at all times anyway, and particularly mothers and calves so as not to fluster them; but frequently the whales will approach you or the current move you.

Calves often mirror the position of their mothers and seem (are) incredibly bound to them. I have one series of photographs from 2015 in which the mother and calf have the exact same position of their pectoral fins over 30 photographs during a 10-minute swim, and it’s incredible to look back.

The sweetest moments are when a calf will settle under its mother’s nose or fin when it’s descended after a breath. Or when a calf rests on its mother’s nose at the surface.

Another fantastic image you will never forget is when mother and calf are side-to-side, touching one another and looking ahead together in unison.

It is very clear when a mother wants an encounter to end. She will whisk her calf away with total determination and sometimes at impressive speed.

Frequently it is the escort, a suitor but not the father, who decides when it’s time to go. He will put himself directly between you and the others or simply move them off.

Sometimes a mother has 2 escorts; but usually – if she has one at all – it’s one. Escorts frequently stay a little in the background or slightly deeper than the mother and calf.

It’s in an escort’s interest to stay close, be protective and to limit competition from other males for the female’s affection.

An escort is frequently more wary of swimmers and keener to interfere than the mother is.

The other typical situation we get is adult whale(s).

Whether one whale or multiple, one sex or both, it’s very distinct from mother and calf and also distinct from a heat run (even if there is such a thing as a mini heat run, which consists of a smaller group of whales).

Sometimes we stumble on a lone individual, sometimes a pair or trio. Their behaviour and the extent to which they interact, whether with you or each other, varies tremendously.

At times, the best you can hope for is to hover over a whale in the water as it rests and watch it rise to the surface when it’s ready to breathe. If you’re unlucky you will experience nothing but this time after time with one whale or group. The whale in question might never turn towards you, interact with another whale, or even come close enough for you to get a good look.

But when they’re good, adult whales can also be amazing.

Photographing - and even seeing - the whales is a real challenge when they’re deep.

In deep, dark water (the waters around Vava’u are generally very deep) it’s hard to identify dark bodies. Much of the time, the only way to notice the whales deep is when the white patches on their sides or their bellies are showing.

Two of my favorite moments are before and while the whales rise. At first, if you haven’t been looking at the white patches on their sides or seen their bellies, you see the tip of the nose and nodules on it. Sometimes the nose is paler, which helps to see, and sometimes not.

But as they rise the nose becomes bigger and bigger in your sight. You realize how big and graceful the whales are with every second they come closer to you, every meter closer to the surface. And you can’t understand for the life of you why those nodules are there or what function they serve.

The other thing I love about watching the whales when they’re under is the decision point - or multiple decision points - before they rise.

Their pectoral fins are perpendicular from their sides when immobile or resting; but they have to bring the fins towards each other before they rise. There is always a first flutter of the fins, like the beginning of a decision, before multiple consecutive flutters or just a slow concerted pull into the rising position.

As they rise the whales decide where to turn – towards you or away from you. And if you’re lucky they will come directly towards you, head to head, or rotate on their axis to show you their white undersides before they turn away.

Sometimes they hang… Most of the whales spend all their time below the surface horizontal, only going vertical to rise. Others stay vertical, as if just waiting at the ready, much of the time below the surface. One mother a few seasons ago had her head pointing to the bottom and tail to the sky!

Sometimes they roll… Roll over, whether horizontal or vertical, and show you their beautiful, white stomachs and throats — ridges of skin and all.

For friendly and interested calves, rolling seems quite frequent — like they’ve learned a new trick, are practicing and showing off at the same time.

Sometimes an adult will roll as well… or even roll repeatedly as you swim next to it. In the case of an adult rolling it really feels like an intentional and highly conscious thing, as if they’re doing it for you... whereas calves might be doing it for their own amusement as much as yours.

Sometimes whales CHASE you or rush you!

“Crazy George” was practically pushing me, his eye a meter from mine and nose against my flipper, on a swim in August last year. I tried to swim away from him as fast as I could three times, but each time he was still right on me. Crazy George has been known to lift people out of the water on his head!

Another whale, our first of the season two years ago, saw my guide Alistair Coldrick and me and that very second rushed us as fast as he could. He/she rushed us at high speed from about twenty meters away until he/she dove about 5 meters in front of us!

And then again this year: we had TWO whales acting crazy on an encounter with us. One of them kept turning towards us as we swam parallel to it — constantly forcing us to turn and getting too close for comfort (no one wants to hurt an animal. Nor be hurt by one) — And nearly lifted my friend on its pectoral fin. The other whale stayed far off for most of the time but would then suddenly come into the mix, unexpected, from out of the blue, jarring us with its speed and unpredictability.

Sometimes they breach… One usually only sees breaching from fairly far away – as one does tail slapping and fin slapping at the surface. It’s rare to have a whale breach close to you while you’re in the water. But it can happen. Unfortunately it’s also rare that the whales stick around and interact with you after they’ve been playing at the surface, slapping or breaching, for minutes. Even when it looks like they’re inviting you to come in and join them, they often let you down by swimming off!

Sometimes they float up… This summer, we saw a calf so young and inexperienced that it was still working on its buoyancy. Instead of gently tilting toward the surface headfirst, it floated up bottom first with nearly no control!

Sometimes you don’t even notice how a horizontal whale below the surface suddenly got 6 meters closer to you without having visibly moved. As if the animal can rise without making a single effort.

The visibility in the water can be remarkably bad – this has been the case during 2 of the 5 seasons I’ve visited – and a large number of images of the Vava’u whales you see on the Internet, including by lauded and well-known photographers, are massively touched up.

As often as possible I keep my images nearly entirely true to the situation they were taken in. But in most cases you don’t want dozens of green strands in your whale picture.

We swim hard in Tonga! Looking at beautiful images during the off season allows you to forget how hard you swim for them. You sometimes remember immobile mothers and calves that took no energy and forget a heat run that took seven swims out of you.

But each experience is worth every kick.

Swimming with whales is unbelievably rewarding. As corny as it sounds… the whales do “change your life”. They’re simply too majestic, too enormous, too touching and too intelligent not to.

Just as with humans there’s virtually no way to assess or predict an animal’s character, mood or behaviour ahead of time.

Some days “Crazy George” might just want to swim around in peace. Some days a reserved whale or introspective dolphin might experiment with you, might be in a fun mood and decide to play.

Likewise there is no understanding why one mother whale will be so nervous and worried and swim away at light speed at the sight of a swimmer, whisking her calf away, where another mother chooses to just stay put, unflinching and relaxed, while multiple people observe with joy as her calf swims about unbridled and unconstrained.

Everything depends entirely on the individual.

It might take 6 different whales that are mediocre or flee before you find one great one that doesn’t.

Sometimes you try the same animals that are completely disinterested several times before their mood changes and they suddenly give you magic.

With the dolphins in the Bahamas it’s the same principle. Sometimes there are 20 dolphins in the water and they disappear when you jump in.

Sometimes only 2 dolphins and they stay with you for 3 hours. Sometimes you’re with one group of animals and another one comes from nowhere and joins in.

And on some days you don’t see a single animal at all.

1. Nine out of ten restaurants are closed. Not a single work boat, whale or other guide goes out on Sunday

2. Bellavista’s lovely staff includes waitresses Jay, Eta, Seini and Taina.

3. I was told recently that a whale in Moorea stayed down for 40 minutes at one point this summer.

“Synchronized mother and calf swooping in.”

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

The calf was only about a meter below my flippers when it passed under me!

We were only with these guys for a short time.

We rarely see the whales in such shallow water, making this image a little exceptional.

I was surprised that they didn’t choose an alternate route!

Some of the images of them directly underneath me are a bit more interesting, less typical, than this one. The calf’s tail, which seemed enormous, was mottled, and looked a strange tinge of grey-yellow.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

The calf was only about a meter below my flippers when it passed under me!

We were only with these guys for a short time.

We rarely see the whales in such shallow water, making this image a little exceptional.

I was surprised that they didn’t choose an alternate route!

Some of the images of them directly underneath me are a bit more interesting, less typical, than this one. The calf’s tail, which seemed enormous, was mottled, and looked a strange tinge of grey-yellow.

A humpback whale calf swims above its much larger mother, with the male “escort” trailing behind.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2014

I love how the mother’s eye looks surprised.

The escort is not necessarily the calf’s father; but usually an attentive (and protective) suitor to the mother.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2014

I love how the mother’s eye looks surprised.

The escort is not necessarily the calf’s father; but usually an attentive (and protective) suitor to the mother.

“Touching moment” – Humpback calf and mother

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2014

These were the first whales I ever saw underwater!

The calf was very small – very young – and I couldn’t believe the extent of the love I was witnessing between these animals.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2014

These were the first whales I ever saw underwater!

The calf was very small – very young – and I couldn’t believe the extent of the love I was witnessing between these animals.

Mother and calf ready to rise --

In the deep waters off Vava’u

Tonga, august 2015

The curvature comes from a fisheye lens…

The water must have been very clear that day, the visibility great.

It has not been good at all the past 2 seasons.

The rays of light shining into very deep water are beautiful. So beautiful in fact that I occasionally just shoot the rays themselves – or the dark blue spot they converge to below you.

The calf in this image is fairly large, so not one of the youngest ones. Younger calves are very small (in comparison to adults that can reach 15 meters of length!)

Usually calves are significantly lighter than their mothers for reasons I don’t know, which makes this particular calf stand out as different.

In the deep waters off Vava’u

Tonga, august 2015

The curvature comes from a fisheye lens…

The water must have been very clear that day, the visibility great.

It has not been good at all the past 2 seasons.

The rays of light shining into very deep water are beautiful. So beautiful in fact that I occasionally just shoot the rays themselves – or the dark blue spot they converge to below you.

The calf in this image is fairly large, so not one of the youngest ones. Younger calves are very small (in comparison to adults that can reach 15 meters of length!)

Usually calves are significantly lighter than their mothers for reasons I don’t know, which makes this particular calf stand out as different.

A Humpback mother and her calf on their ascent, lit up by sun rays.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

The 2015 season was by far the best visibility of my 5 summers in Tonga.

This humpback duo was in ultra-clear water quite a distance away from port.

We never know where we’ll find the whales (if any whales) on any given day. Sometimes we see them a kilometre from home -- Neiafu, right after we leave (at 7 or 7:30 a.m.). Sometimes we are an hour or more away.

Visibility is sometimes very mediocre or even really bad. Particles are extremely obvious in sunlight.

Entire seasons can be bad for photography. In 2019 we had strands of green matter everywhere in the water, and for any image to look good the water will need to be significantly digitally cleaned up; colour contrasts probably enhanced.

It’s surprising how much organic matter can be in Vava’u waters … and it seems almost unbelievable that the whales don’t actively feed there.

The calves suckle; but adults eat elsewhere.

In this image I love how detached the calf seems from its mother, almost as if it carried its own light with it.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

The 2015 season was by far the best visibility of my 5 summers in Tonga.

This humpback duo was in ultra-clear water quite a distance away from port.

We never know where we’ll find the whales (if any whales) on any given day. Sometimes we see them a kilometre from home -- Neiafu, right after we leave (at 7 or 7:30 a.m.). Sometimes we are an hour or more away.

Visibility is sometimes very mediocre or even really bad. Particles are extremely obvious in sunlight.

Entire seasons can be bad for photography. In 2019 we had strands of green matter everywhere in the water, and for any image to look good the water will need to be significantly digitally cleaned up; colour contrasts probably enhanced.

It’s surprising how much organic matter can be in Vava’u waters … and it seems almost unbelievable that the whales don’t actively feed there.

The calves suckle; but adults eat elsewhere.

In this image I love how detached the calf seems from its mother, almost as if it carried its own light with it.

Bumping into a delightfully curious Humpback whale calf

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

This calf bumped my friend Trevor first, then made a slow pass by me.

Its pectoral fin was actually touching me while this image was being taken!

It felt to me as if time had slowed down for this interaction.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

This calf bumped my friend Trevor first, then made a slow pass by me.

Its pectoral fin was actually touching me while this image was being taken!

It felt to me as if time had slowed down for this interaction.

Mother and calf Humpbacks

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

Every time I see this image all I can think about is the space shuttle on a Boeing a few decades ago.

Nothing more.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2015

Every time I see this image all I can think about is the space shuttle on a Boeing a few decades ago.

Nothing more.

“This was not the calf’s first breath"

A humpback whale supports her calf at the surface

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2017

I must have spent a good 30-40 minutes swimming with this mother and calf duo. They were magnificent — and moving fairly slowly.

I took so many photographs that at one point I had to ask the guide to get my second camera!

This was definitely not the calf’s first breath — and I’ve now observed this behavior at least 2 other times.

While I'm certain that this calf is days, if not weeks, old: I have no idea how to judge the age of a whale calf.

The guides are much better at that… and often have an idea based on whether the calf has been seen before — and for how long.

Just like with humans and other animals, humpback calves are born at different sizes — and the guides nearly always tell us when a calf is particularly small.

Humpbacks are in Tonga from approximately June through late October or early November.

Apparently October is a good month to see mothers and their calves as the calves are more confident and playful.

A humpback whale supports her calf at the surface

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2017

I must have spent a good 30-40 minutes swimming with this mother and calf duo. They were magnificent — and moving fairly slowly.

I took so many photographs that at one point I had to ask the guide to get my second camera!

This was definitely not the calf’s first breath — and I’ve now observed this behavior at least 2 other times.

While I'm certain that this calf is days, if not weeks, old: I have no idea how to judge the age of a whale calf.

The guides are much better at that… and often have an idea based on whether the calf has been seen before — and for how long.

Just like with humans and other animals, humpback calves are born at different sizes — and the guides nearly always tell us when a calf is particularly small.

Humpbacks are in Tonga from approximately June through late October or early November.

Apparently October is a good month to see mothers and their calves as the calves are more confident and playful.

Humpback calf, pre-bump!

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2017

Some calves bump you when they come near.

It doesn’t hurt and they mean you no harm.

I think sometimes they do it for fun.

That young they might also be a little clumsy.

Inadvertent.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2017

Some calves bump you when they come near.

It doesn’t hurt and they mean you no harm.

I think sometimes they do it for fun.

That young they might also be a little clumsy.

Inadvertent.

Sometimes they go diagonal…

This calf, from our August 2017 trip, was extremely curious and interactive.

Vava’u, Tonga

Humpbacks keep their eye on you even as they roll. Sometimes you notice them staring at you at the most unlikely time… and when you think they’ve got over you, having long accepted you as a strange dolphin or fish.

Protective mothers in particular pay close attention to you, their eyes staring straight at you even when the eye is the body part the furthest away from you.

I love the dark patch centered on this guy (or girl)’s throat…

This calf, from our August 2017 trip, was extremely curious and interactive.

Vava’u, Tonga

Humpbacks keep their eye on you even as they roll. Sometimes you notice them staring at you at the most unlikely time… and when you think they’ve got over you, having long accepted you as a strange dolphin or fish.

Protective mothers in particular pay close attention to you, their eyes staring straight at you even when the eye is the body part the furthest away from you.

I love the dark patch centered on this guy (or girl)’s throat…

My friend Tamiko named this humpback, our first of the 2017 season, “attack whale”!

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2017

Perpendicular to us and about 30 meters away at first, it immediately turned to my guide Alistair and me when it saw us -- and swam straight towards us at full speed! It only dove down when it was about 6 meters away…

On our next swim it immediately rushed Tamiko and her group, too!

I’m sure the whale was just having fun… but it’s still intimidating and Alistair still tried to move me out of harm’s way.

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2017

Perpendicular to us and about 30 meters away at first, it immediately turned to my guide Alistair and me when it saw us -- and swam straight towards us at full speed! It only dove down when it was about 6 meters away…

On our next swim it immediately rushed Tamiko and her group, too!

I’m sure the whale was just having fun… but it’s still intimidating and Alistair still tried to move me out of harm’s way.

A mother humpback turning directly towards me, spreading her immense pectoral fins as she hovers vertical. Her eye was wide open and I could feel the connection, sense her thinking.

Vava’u, September 2017

At times it’s easy to wonder whether whales and dolphins can peer into your soul.

Vava’u, September 2017

At times it’s easy to wonder whether whales and dolphins can peer into your soul.

Meet “Crazy George”!

There is a whale that frequents Vava’u known as “Crazy George” because he occasionally lifts people out of the water on his nose!

Tonga, August 2018

We had two adult whales one afternoon off the boat – both acting normally until one of them came RIGHT UP TO ME, its eye a meter and a half from mine, and wouldn’t leave me alone. I swam away as fast as I could 3 times in a row; but the whale just followed me and stayed on me every time. At one point I saw it dip its head and thought to myself “this must be the lifting whale”. People didn’t believe me about the experience until a local guide recognized the whale’s flukes In a photograph that evening – and confirmed that I’d had a run-in with Crazy George.

Even though I knew George was just another mammal trying to have some harmless fun, it was somewhat terrifying to have a 12-15-meter animal basically chase me – and from less than two meters away!

There is a whale that frequents Vava’u known as “Crazy George” because he occasionally lifts people out of the water on his nose!

Tonga, August 2018

We had two adult whales one afternoon off the boat – both acting normally until one of them came RIGHT UP TO ME, its eye a meter and a half from mine, and wouldn’t leave me alone. I swam away as fast as I could 3 times in a row; but the whale just followed me and stayed on me every time. At one point I saw it dip its head and thought to myself “this must be the lifting whale”. People didn’t believe me about the experience until a local guide recognized the whale’s flukes In a photograph that evening – and confirmed that I’d had a run-in with Crazy George.

Even though I knew George was just another mammal trying to have some harmless fun, it was somewhat terrifying to have a 12-15-meter animal basically chase me – and from less than two meters away!

Possibly the most touching and my best photographed “mum and calf” from the august 2018 trip!

Vava’u, Tonga.

The calves are nearly always paler than their mothers; but sometimes, as is the case here, they have a different pattern entirely.

Last summer (2019) we saw a calf that was completely white other than on its head.

I could instantly tell this was going to be a nice image because of the colour contrast and since the two whales were perfectly lined up and completely immobile.

Vava’u, Tonga.

The calves are nearly always paler than their mothers; but sometimes, as is the case here, they have a different pattern entirely.

Last summer (2019) we saw a calf that was completely white other than on its head.

I could instantly tell this was going to be a nice image because of the colour contrast and since the two whales were perfectly lined up and completely immobile.

Just another lovely calf doing its rounds, watching us from close…

Tonga, August 2018

Tonga, August 2018

Some of the most beautiful light I’ve ever seen and one of the most rewarding post-effort, post-disappointment moments.

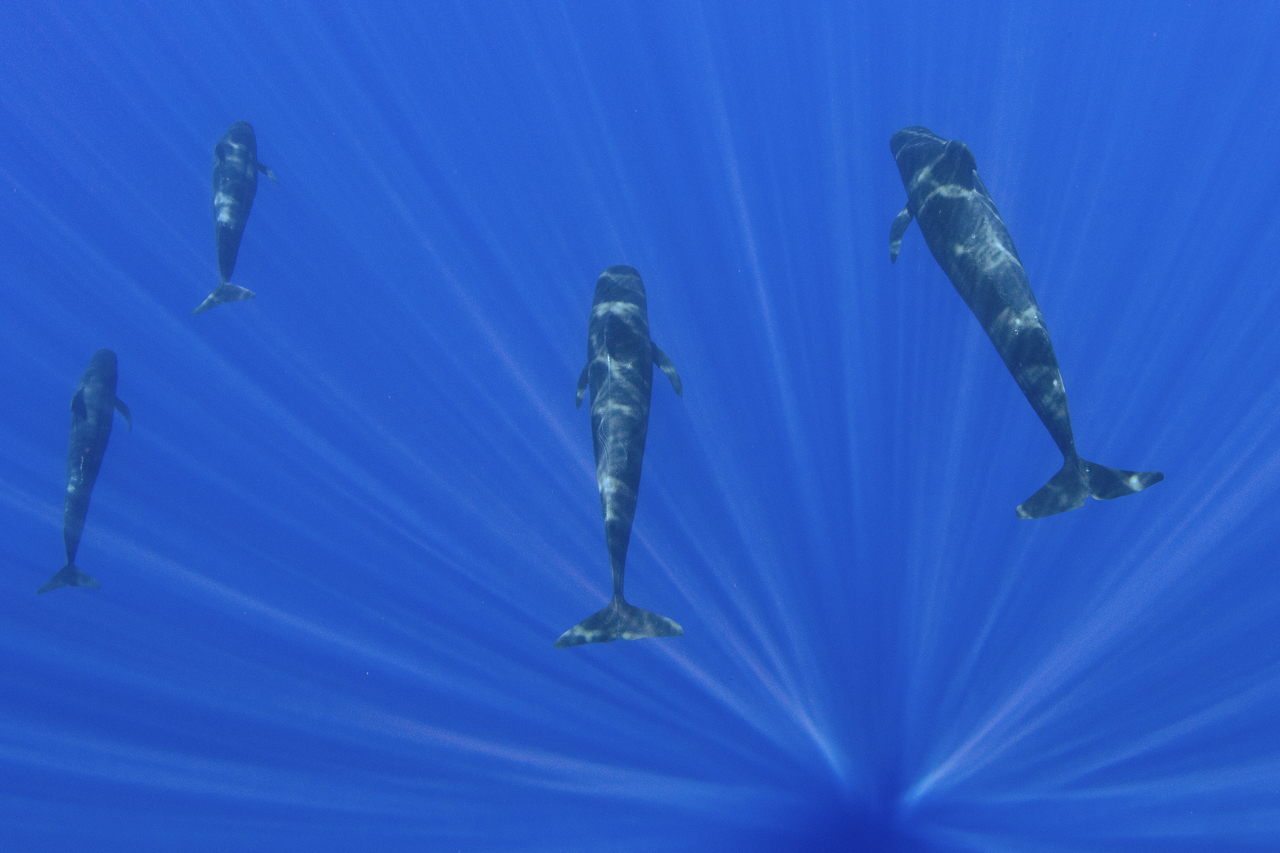

Pilot whales swimming in shards of light off the coast of Moorea, August 2019

My guides and I jumped in the water at least 14 times over 2 afternoons in the hopes of photographing these whales. Pilot whales are famous for swimming down – avoiding you - as soon as they see you at the surface.

And this was our sad experience again and again. But during two swims the pilots travelled through beautiful sun rays below us and it made for the nicest pictures!

At the end of the second afternoon we were even lucky enough to float about motionless with maybe 12 pilot whales that were just resting there, barely under the surface!

And that was one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve ever had – particularly after so much repeated effort and disappointment.

Pilot whales swimming in shards of light off the coast of Moorea, August 2019

My guides and I jumped in the water at least 14 times over 2 afternoons in the hopes of photographing these whales. Pilot whales are famous for swimming down – avoiding you - as soon as they see you at the surface.

And this was our sad experience again and again. But during two swims the pilots travelled through beautiful sun rays below us and it made for the nicest pictures!

At the end of the second afternoon we were even lucky enough to float about motionless with maybe 12 pilot whales that were just resting there, barely under the surface!

And that was one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve ever had – particularly after so much repeated effort and disappointment.

One special view from our endless swims with pilot whales

Moorea, August 2019

During one of our last swims with pilot whales they’d started to slow down, making it much easier to photograph them (and breathe!). I was even lucky enough to be able to swim neck and neck with them for a short time – and this is an image from that happy moment.

Moorea, August 2019

During one of our last swims with pilot whales they’d started to slow down, making it much easier to photograph them (and breathe!). I was even lucky enough to be able to swim neck and neck with them for a short time – and this is an image from that happy moment.

“Goodbye, human!”

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2019

Vava’u, Tonga, August 2019

A humpback blows bubbles during a heat run in August 2019.

Vava’u, Tonga

Blowing bubbles is a sign of aggression/threat in humpbacks.

Heat runs are when multiple males are pursuing a female to mate with her – up to 18 males or more chasing after one female!

I assume this was a male whale trying to intimidate some of its competition.

Or voicing its frustration!

It’s a shame about the tail being cut off in this image; but it’s the best bubble image I have!

Vava’u, Tonga

Blowing bubbles is a sign of aggression/threat in humpbacks.

Heat runs are when multiple males are pursuing a female to mate with her – up to 18 males or more chasing after one female!

I assume this was a male whale trying to intimidate some of its competition.

Or voicing its frustration!

It’s a shame about the tail being cut off in this image; but it’s the best bubble image I have!